Ramada Express Rally 2000

170 stage miles, one beater rally car and the worlds biggest hammer.

From the February, 2000 issue of Sport Compact Car Magazine

By Dave Coleman

Photography by Dave Coleman

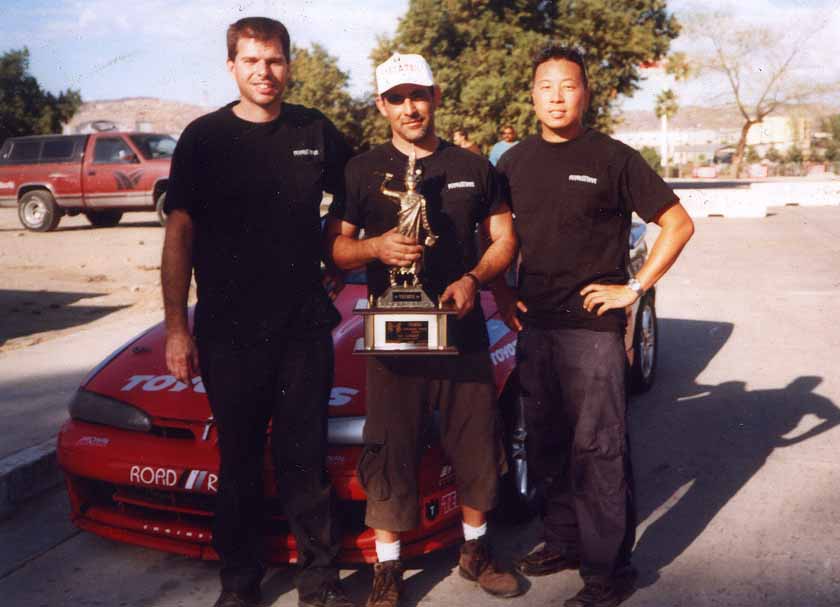

It’s a phrase no rallyist wants to utter.”Uh, Mike, can we borrow a hammer?”Mike Welch, of Road/Race Engineering, has along with his unhealthy fondness for fixing smashed rally cars, the world’s largest collection of rally car repair tools. Among them is The Hammer. The Hammer is a mangled, 60-LB block of lead impaled on the end of a Ford truck axle. We already knew The Hammer. We had seen it back at Road/Race’s shop and had even been known to pick it up just for fun, or point and giggle at the though of actually using a thing to fix a car. We weren’t laughing now.

Welch let us borrow The Hammer, but that was only the first hurdle. Next we had to swing it. The Hammer, when you count the handle and the various pieces of rally car shrapnel embedded in it, weighs at least half as much as the heftiest member of our Eyesore Racing Team.

Before long it seemed we had a carnival barker calling out, “Watch the big hammer swing the nerds!” A crowd had gathered to eye our vinyl topped shoebox of destruction with the mix of sympathy and humor appropriate for its current state. Bent, rally sore, and wheels akimbo, Project Rally Beater was coated with equal parts dirt, glory and despair. The despair was only getting thicker as, one after another, our 160-pound driver, 130-pound navigator, and 130-pound crew chief strained muscle and tendon to gently tap The Hammer against the rear wheel.

Then the crowd parted, and through the gap appeared Bob DeBenedetto. Spectator, rally nut, and easily 300 pounds of solid muscle, DeBenedetto probably could have bent our suspension back into shape with his hands. With a soft spoken “mind if I try?” he picked up the hammer lined it up with the top of the rear wheel and took a swing. The first hit was so hard the car jumped in the air. Dust gently wafted out of every crevice in the bodywork. But most importantly, the top of the wheel moved in about half an inch. He hit it again, and again, and again. “Hit it a little higher, a little farther forward, a little farther back.” With the precision of a laser alignment rack, The Hammer pointed the wheel back where it needed to go.

Back to Welch for another beg. With a welder borrowed from one team and a generator borrowed from another, Welch welded up the new crack in the control arm and that was it. With 10 minutes to spare, our rally was back on track and we were ready for the longest stage in American rallying.

The hammer incident was the culmination of a year’s worth of half-hearted preparation, corner-cutting and making do.

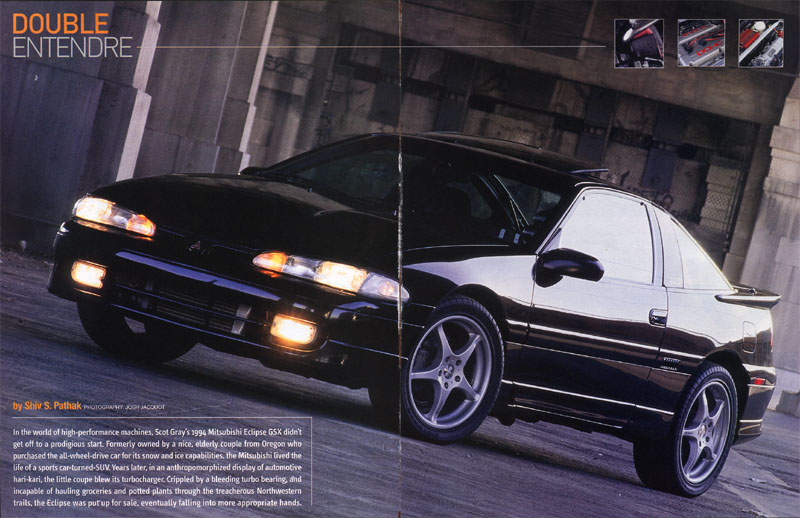

After noting the cheery disposition of a rally driver who had just tossed his car high into a pile of rocks at the 1999 Ramada Express Rally, it quickly became obvious that the true path to rally happiness was not through a WRX or Lancer, but through a Corolla, RX-7, or other suitably disposable beater.

Beaters can be flung against the rocks with wild abandon and then repaired for pennies–or replaced with another beater.

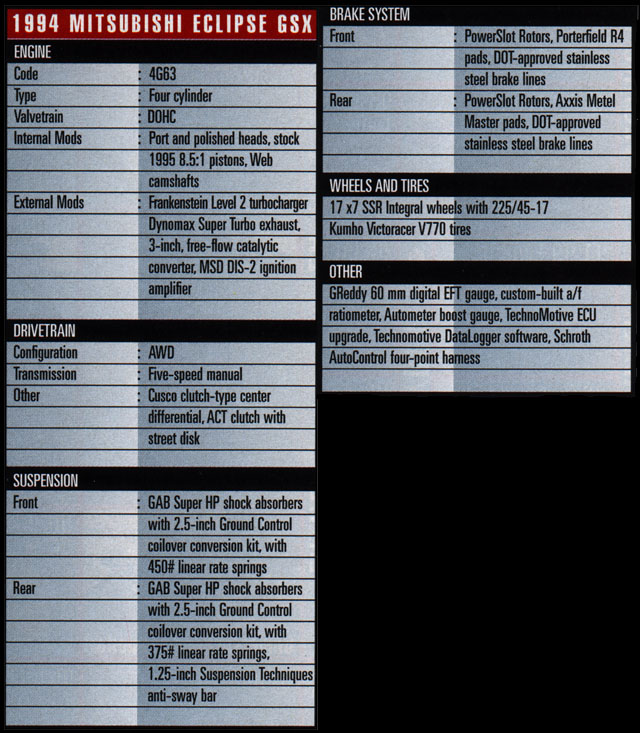

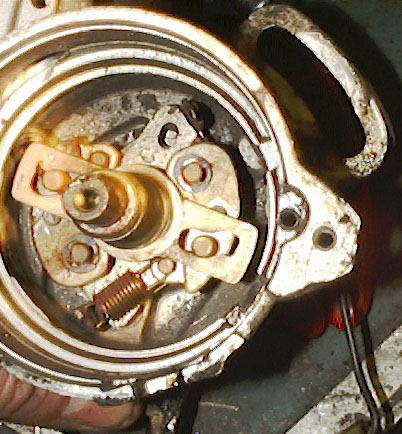

It was after watching this very rally in 1999 that we decided to build a beater ourselves. That we returned to the Ramada Express to race in 2000, however, was unexpected. The Beater’s first official competition was in the Treeline ClubRally, a local event so close to home that we didn’t need a trailer. At that point, the car was barely ready for competition, and the notion of being robust enough to finish a 46-mile rally was questionable at best. The 160-mile, three-day Laughlin event wasn’t even a consideration. But in the adrenaline of the moment, after most of the car proved somewhat durable (we did have a distributor failure that put us into last place for two stages) we gleefully proclaimed “We’re going to Laughlin!” Oh boy.

Of course, this event, officially dubbed the Ramada Express Hotel and Casino International Rally presented by Mitsubishi, is a much larger undertaking than Treeline. Treeline is six stages in one day, Laughlin is 15 stages in three days. Treeline is 47 stage miles, Laughlin is more than 160, with stage 11 alone totaling 45 miles. We had a car, now we needed serious logistics.

First lesson of rally logistics: Don’t make fun of your friends for driving trucks. When our longtime friend Jeff Payne traded in a Impreza 2.5 RS for an extended cab, four-wheel-drive Cummins turbo diesel pickup, we naturally unleashed the full force of our SUV hatred on him. Lucky for us, he has a short memory. You can fit a lot of rally car parts in the back of a Dodge truck, and the Cummins engine doesn’t even notice a rally beater on a trailer. Oh, and about that trailer. What’s an aspiring rally driver with limited parking supposed to do about trailers? We rented one from U-Haul for about $260 for five days.

And then there’s clutch paranoia. It isn’t a universal problem, but it strikes us before any long event. One Lap of America, 1999: Our WRX RA had been passed around to various members of the press for three years, and the clutch seemed to engage a little more softly than it should. Paranoid about a mid-race clutch failure, we talked Subaru into air freighting a new clutch from Japan and installing it one day before the car was shipped to the race. The old clutch, naturally, was less than half worn.

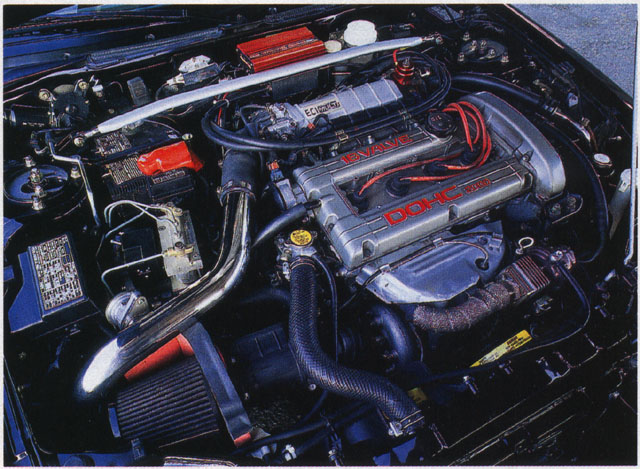

So it was with the Rally Beater. We had installed the engine only a few hundred miles before and the clutch, though worn, was far from ready for retirement. But somehow it suddenly didn’t seem to grab hard enough to give us confidence. A week before the rally, we frantically called Centerforce. Project Rally Beater has a clutch from a 2000 Datsun Roadster, an extremely rare car these days, but Centerforce not only makes a clutch for the Roadster, it was able to have it in our hands in less than two days! Now, that’s a pretty comprehensive product line! Working under a rally beater is an adventure in dirt. Removing the transmission after a rally means enduring an avalanche of gravel and mud every time you touch something, but in a few frantic hours, we had the old clutch out and the new one in. Naturally, the old one appeared to have plenty of life, but the two 30-foot black stripes on the street outside the office suggest the Centerforce is still far stronger.

And then there are the spare parts. At Treeline, we packed light. The only spare part was a distributor, which, as luck would have it, was the only part to break. For Laughlin, we packed everything. Digging around under shelves and behind workbenches revealed a treasure trove of forgotten parts. Spare engine mounts, brake drums, struts, steering linkages, alternators, starters, lights, hoses, fluids, anything and everything was put in plastic bins and labeled for the inevitable late-night repair sessions. Preparation for the rally was an all-consuming effort, mixing equal parts of paranoia and giddy excitement.

Naturally, the preparation didn’t end at getting the car to the event. We still had to unload it and pass tech. Normally, the pre-rally tech inspection is fairly minimal. The harnesses and roll cage were checked, the certification on your helmet and driving suits are reviewed and, because transit stages are often run on public roads, a basic check of headlights, horn, turn signals and brake lights is performed. No sweat, right?

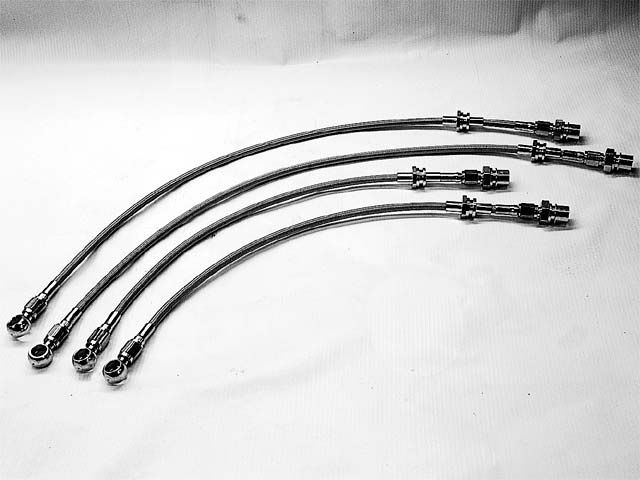

Naturally, after 30 years of working perfectly, the brake lights chose to fail just as we were waved into the inspection. We got through (don’t ask how) and the preparation continued.

Word around the pits was that the first day’s forest stages were covered with snow and mud. Tomorrow was going to be a race of survival. Hmm, used, warm-weather rally tires, an open differential and snow. We stopped thinking about finishing well and started thinking about finishing at all. Five minutes before closing time, we came squealing into the last open auto parts store in town and bought tire chains. Is this an odd sport or what?

Then, we saw Rhys Millen preparing for the soggy mud/snow soup by cutting larger grooves in his nice, new Michelin rally tires. After a quick, tire-grooving tutorial from Millen, we borrowed a tire-gooving iron from fellow rallyist Paul Timmerman and started work on our tired, old Silverstones. Rallies have specific rules mandating when and where teams can work on their cars. In parc expose, teams may work on their cars as they are displayed to the public. However, in parc ferme, the car can’t be touched. Parc ferme began at midnight, and we finished grooving tires at 11:59 pm. The parc ferme rule never made sense before then; without this rule, we probably would have worked through the night.

The transit stages for the Ramada Express Rally are huge. All the stage roads are on the Hualapai Nation on the edge of the Grand Canyon, about 100 miles from Laughlin. In previous years, drivers had complained about the fatigue, monotony and tire wear from the long transits, so the rules were changed this year to allow the cars to do the long transits on their trailers.

To make the race look more exciting for the locals, however, all the cars still drove over the start ramps and through town before loading onto the trailers across the border in Arizona. The American Rally Sport Group has a good record of trying to keep the competitors happy and the rally as spectator-friendly as possible.

Expecting mud, snow and slush on narrow forest roads, we pulled up to the start of stage one and saw a dry, hardpacked straightaway. Just before counting down to our start time, the starter warned us that two cars have rolled on this stage. No pressure… Go!

At approximately 7,000 feet, the Beater accelerated reluctantly to a top speed of about 80 mph. On the dirt, with thoughts of cars on their roofs, it still seemed really fast. After a few minutes of driving flat out, the road suddenly narrowed, got wet and snowy, and turned into a hard right. Less than 10 turns into the twisties, we saw warning triangles, an OK sign, and the Audi quattro of George Plsek and Alex Gelsomino tires up in the ditch. It took serious self control to keep the car on the road as we worked slowly up to speed. An upside-down car on the first stage doesn’t inspire confidence. A few turns later, the scene is repeated, this time with Mark Nelson and John Bellfleur’s Mitsubishi Lancer. This was getting ugly.

When we reached the end of the stage, the arrival time control was at the top of a very small hill, and another car was still busy checking in. We waited halfway down the hill, and then tried to pull forward when the other car moved. We tried.

Even on the very slight incline, we just sat and spun our tires in the mud. Just making it to the time control meant backing up and taking a running start. This was an omen.

Everything was brown. The road was brown, the cars were brown, the trees were brown, the windshield was brown. The road was heavily rutted, but the ruts were nearly impossible to see. They constantly tugged the car this way or that, and steering inputs seemed to have little effect in this slime.

The transit to stage two had two-way traffic, with the leaders, having already finished the second stage, coming head-on toward us on their way to the first service stop. Common sense said to slow down, physics said if we did so we’d get stuck, so there we were, flying through the muck, tires spinning, car sliding erratically from one side of the road to the other. Rhys Millen was doing the same, and we narrowly miss slamming head on into him. As our windows passed within inches, we could see the grin on his face was almost as big as ours. Insanity loves company.

The start of stage two was frozen and slick. So slick, in fact, that as Richard Byford and Fran Olson tried to inch forward to the start, their BMW 2002 did a slow, graceful pirouette and ended up stuck sideways in the road in front of us. Several navigators jumped from competing rally cars to push them from the muck.

The weighty slime so thoroughly coated the sides of our car that the stage workers had to ask our car number before recording our times. Our hearty mudflaps, which had survived all our “testing and development” miles without complaint, were ripped from the car after just two stages in the slime.

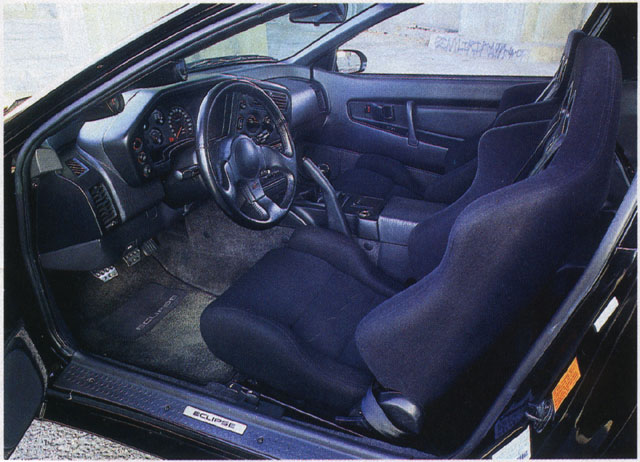

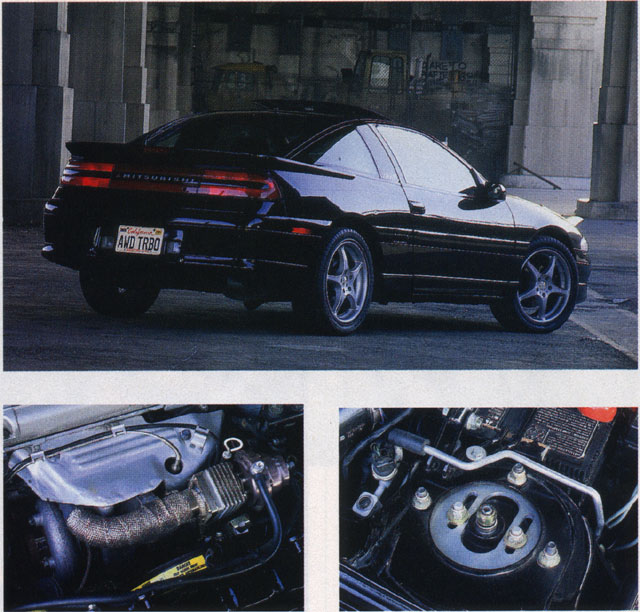

Stages three through six were more of the same–slimefests of epic proportions. The mud became so thick at one point that full throttle in The Beater produced all of 35 mph. At the end of day one, The Beater managed an impressive 10th overall, slotting in right after the open class Galant VR-4 of Keith Roper and Ray Damitio and sneaking in just in front of the Group 2 Eclipse of Christopher Burns and Steve Westwood. The next day was sure to be harder for The Beater as the roads opened up and horsepower became more of a factor.

Faster it was, though momentum was proving itself a fair substitute for horsepower for a while. Pounding up stage 7 out of the grand canyon, we managed to hold our position despite the need for power. After a brief roadside repair stop to fix some loose exhaust bolts, we started into the real horsepower stages where the fast cars were going 140 mph, and we were going 100. That lead directly to the ditch (see “Great Moments in Rallying #3, to the right.)

Driving fast on treacherous, slippery roads you have never seen requires a certain placidity, a certain Zen calmness in the face of unparalleled pressure. Every road has a rhythm, every car has its special moves, and being in the zone means being able to make the car dance. Try dancing after crashing a car, running a quarter mile with a helmet on your head and the thin air of 6,000 feet in your lungs, after spending five minutes jumping around in a ditch like a couple of drunk monkeys. This is the kind of challenge that separates the professionals from the dirt jockeys like us.

The very next stage, still breathing heavy, and still searching for our rhythm, it happened again. This time there was no glorious almost-save. This time it was simple. We went too fast, turned too late, and slid into a small ditch. A very hard small ditch. This, for certain, was the end of the rally for Eyesore Racing.

This brings us up to The Hammer, but you’ve already heard that one. Finishing the Laughlin rally’s 45-mile Canyon Challenge stage after repairing the The Beater with The Hammer may turn out to be the crowning achievement in our motorsport careers. The Canyon Challenge came at the end of the day as the sun was setting. And, as luck would have it, the stage ran primarily east to west. That meant the pucker factor was high as The Beater blasted over blind crests, directly into the blinding sun. However, this time, it stayed on the road and made it to the end of the second day.

Leg Three of the Laughlin event is held in a huge gravel field behind the headquarter’s hotel. It’s called the SuperStage and is basically a dirt autocross which pits competitors against one another in wheel-to-wheel brawls designed to put a spectator-friendly finishing touch on the event. Organizers match cars which have produced similar stage times on the rally’s previous legs to compete together on the two-lane SuperStage course.

The Beater was matched against the RX-7 of Jim Gillaspy and Mick Kilpatrick who had eeked out a fair lead on us the previous two days. The SuperStage, however, proved how well matched the cars really were as the two were given the exact same finishing time on two of the four stages. Naturally, Gillaspy’s car was slightly ahead on those runs, but a half car length is invisible in rally time. The other two runs were a draw–one win each. Stage 15 brought to an end one of the longest, roughest and highest attrition races in American rallying in the last 10 years.

In the end, The Beater did all right. Somehow, despite all our efforts to throw it away on stages 10 and 11, The Beater won its class (Group 2) and managed ninth overall–not bad given the number of four-wheel-drive open class cars in this race. And the reward for winning Group 2? One thousand glorious greenbacks! Who says rallying doesn’t pay? The ARSG gave away $25,000 in cash and prizes at the awards ceremony after the race.

The organizers of the Laughlin rally have a slogan: “We promise you an adventure,” they say. And given the roads, distance and fun factor of this year’s event, we couldn’t agree more. The Laughlin International Rally epitomizes what rallying should be: Man vs. road vs. the clock. It is, without question, an adventure.

Read more: http://www.modified.com/projectcars/0107scc_ramada_express_rally_2000/index.html#ixzz1hEqXbxeX