Sport Compact Car Magazine 1994 – Reprinted with permission

By Mitch McCullough

We were halfway through the eighth stage of the Lake Superior PRO Rally and things weren’t going so well. A misfire in the engine, caused by a faulty throttle position sensor had reduced our power. Then a problem with the clutch linkage made shifting difficult. So I wasn’t too surprised when a Mazda 323 GTX piloted by a fast local driver started catching our 323 GTX.

Our PRO Rally effort had been going extremely well up to this point. I had bought the partially prepared 1988 Mazda 323 GTX just before the 1993 season started, and codriver Scott Webb and I had won the 1993 California Rally Series championship. We had raced against some strong competition and it was the first time in the 18 year history of the series that a driver had won the championship in his rookie year. Webb and I were each named Rookie of the Year.

We went on to clinch the 1994 SCCA Southern Pacific Divisional Championship, which starts and ends on Labor Day. This title earned us an invitation to compete against Divisional champions from around the country at the Press On Regardless PRO Rally in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, a vast wilderness of deer, trout and the kind of dirt roads all rallyists dream about.

This year, “the oldest, meanest, toughest” rally in America was renamed the Lake Superior PRO Rally. The Detroit Region SCCA, which had organized the Press On Regardless for 47 years, opted to pass the event on to the more strategically located Lake Superior Region, but retained the POR name for a road rally.

Despite the name change, it was the same event with many of the same dedicated workers and the same phenomenal roads. This year’s rally comprised 165 miles of special stages with another 288 miles of transits.

Stage Eight, called Far Point, began as a fourth and fifth gear run through the dark forests. The powerful driving lights filling our mirrors were mounted on the GTX driven by Craig Sobczak of nearby Marquette Mich. Our clutch would not fully disengage, so shifting was difficult. I was staying in fourth gear, lugging out of the slower corners and not shifting up to fifth on the longer straights, trying to avoid damaging the new close ratio gearbox. We had decided to simply drive for the finish.

It was a dark, rainy night and there was still a long way to go. I had lost my enthusiasm for the high speed stages. “You were driving like an old lady,” Webb said later.

When Sobczak got close, I turned on the right blinker and moved toward the right side of the dirt and gravel road, slowing to 70 mph to let him by. But watching Sobczak throw his GTX through the high speed corners inspired me to go faster. “This is like road racing,” I shouted.

Still, Sobczak was pulling away, dropping momentarily from sight around a bend. On the next straightaway we saw that his left taillight lens was missing and the gap between us had narrowed. Then we saw some tracks in the road where someone had skidded toward the ditch. “He went off and tagged the bank!”

Sobczak had slowed only slightly, but we had turned up the wick and cut our distance. Then Webb called an acute right hand corner where we turned off the smooth county road onto a muddy, slimy trail that went up a hill. A crowd of spectators had gathered, standing behind a yellow banner to witness this challenge.

As Sobczak turned in, his 323 bogged in the muddy turn. Seizing the opportunity, I turned inside and went by him, slinging mud in all directions, and accelerated away. Cameras flashed, the crowd cheered-this was racing!

The path we were now on was composed of the slipperiest mud I’d ever seen. Suddenly, I was switched on and the car seemed to be working much better at the lower speeds. We were shifting from second to third and back again, grinding gears, braking in the muck for the tight turns, the car fighting every change of direction as we squeezed through the trees on the narrow path, grappling for grip. We pulled away from Sobczak and when we finished the stage we were ecstatic. We knew we had lost the stage to Sobczak, but we felt as if we had won the race. It was the highlight of the event.

We failed to press on, however. On the next stage we hit a big rock that cracked the sump, draining our engine’s life blood and ending our race through the dark north woods. Veteran John Buffum won the rally in Paul Choinere’s Audi Quattro. Meanwhile, Rhees Harris from Vemmont beat us to take the overall Divisional driver’s title in the Open 4WD class.

I was surprised at my lack of disappointment over failing to finish the event. It had been a great season and we had prepared well, given our meager budget. In nearly two seasons of PRO Rally, we had not suffered any mechanical problems and were happy to gang them all up in one event. And at the awards breakfast, we learned Scott had amassed enough points to take the overall co driver’s divisional championship in our class!

How We Started

I bought the 1988 323 GTX from Bill Morton, a New Zealander who helped prepare Rod Millen’s 323s for the Asia Pacific series. He had built the GTX for his own rallying pleasure and was forced to sell it after taking a job with Toyota Team Europe. He lamented-and I reveled-in the fact that he had only tested the car once and had never gotten a chance to race it.

But Morton had prepared it well. He removed the interior except for the original front seats, door panels and dash. He and Mike Welch welded in a superb roll cage, reinforced with gussets, and painted the interior refrigerator white. Headroom abounded. They bolted on a sturdy skid pan and numerous mud flaps. And they installed an HKS manual boost control and PFC F CON fuel controller to extract additional horsepower from the tired motor.

But the big feature was the suspension: Morton had managed to procure a rally suspension that had been on one of Mazda Team Europe’s 1988 World Rally Championship cars. This suspension was much stronger than the stock setup and the spring and damping rates provided phenomenal handling over loose, rough surfaces. The rally suspension provided adjustable spring perches for varying the ride height and Bilstein competition dampers.

I knew the basic preparation was right. I knew there was a good divisional series in Southern California. I knew I had to have the car. So I bought it, figuring I’d run a few local events. Besides, I reasoned, the car was street legal so I could always use it to run around town.

A mere eighteen months later we had won two championships and had posted finishes in the top five nationally. My experience in autocross, road racing and blasting down the dirt and gravel roads of Eastern Washington and Northern Idaho seemed to have paid off.

The real key to our success, however, was sound car preparation, a crack crew chief and consistent driving.

Rallying What It Takes

Probably no other motorsport requires the combination of car preparation, driving ability, endurance and reliability demanded by rallying. Triumph in the face of adversity is the battle cry of the successful rallyist.

The key is car preparation. A competitive rally car must be fast, tough and reliable. It must be driven consistently fast, with more emphasis on consistency than on speed. PRO Rallies often comprise more than 100 miles of special stages and another 200 miles of transit legs-quite a bit longer than a 20 minute regional road racing event or three minute autocross. Many times we’ve seen drivers go extremely quick in the early stages only to break or crash later in the event. We’ve been guilty of this ourselves.

The car must be prepared to finish events. Too many teams spend too much money on horsepower, overtaxing the gearbox, suspension and brakes. And assuming you can’t afford to spend more than $30,000 for a six speed gearbox, the engine must offer a generous rev range with enough torque at the low end to dig the car out of sandy switchbacks.

Preparing The Rally Car

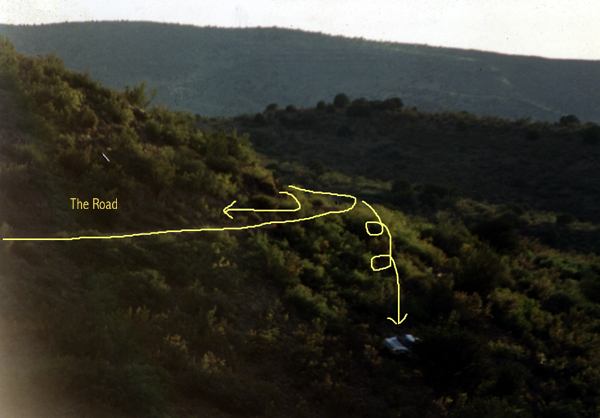

Our 323 suffered two major crashes during the season. In the first one, I mistook the little 323 for a stadium truck and launched it 12 feet into the air at a rally sprint on the Glen Helen, Calif., motocross facility, landing the car on the front bumper. In the second one, we drifted off a sweeper at the Prescott Forest PRO Rally, rolling four times down the mountain.

Most of our development efforts coincided with repair work from these crashes. Road/Race Autosport, a race preparation shop run by Scott Webb and Mike Welch in Los Alamitos, Calif, prepared the car.

Welch replaced the body work and painted the car white with a scheme reminiscent of Mazda’s 1988 World Rally Championship 323s. Road/Race replaced damaged and worn suspension bushings, lateral links, trailing arms, differential mounts and engine mounts using components from Mazda’s Competition Parts division.

Nonslip pedals help a driver keep his feet in place on those rough stages.

The benefit of strut bars is sometimes called into question, but we have witnessed their virtues. The stress of rallying was causing the front strut towers to rotate and gravitate inward. We had gained two degrees of camber and a new fender was off by more than an inch when we tried to match it up to the inner liner. Road/Race solved this problem by designing a front strut bar to tie the towers together. Most strut bars on the market are made of small diameter tubing and often are bent in several locations for clearance reasons, allowing them to flex under the high stress loads. The Road/Race bar is a highly rigid, yet lightweight design with larger diameter tubing and minimal bending between the struts to prevent any flex.

To reduce brake fade and improve reliability, we installed semi metallic brake pads, racing fluid and braided steel lines.

Most PRO Rally cars use a rally computer I to help their drivers keep on time.

Extensive underbody protection is required on a rally car to fend off rocks, tree limbs, flyovers and other hazards, particularly on the rough special stages of the Southwest. Morton’s skid pan protected the sump, and Road/Race added numerous guards made of carbon fiber to protect other areas, while clever metal skids were welded to the leading edges of differential mounts, exhaust joints and important bolts. And all those mud flaps aren’t just for snazzy good looks. A season of flying rocks is like a sand blaster working around the clock that will gradually grind suspension pieces away to nothing. So Road/Race installed mud flaps made of LPDE plastic behind each wheel. in front of the rear trailing arms next to the lower timing chain cover and anywhere else that was exposed to flying rocks. We’re constantly replacing them.

The car came with safety harnesses. so inside we added a rally computer, a pair of racing seats, a padded box for our helmets, window nets on both sides, an intercom and a co-driver’s map light with a red lens-a white light is distracting for the driver and is too bright for the white paper in the co-driver’s route book.

Road/Race replaced the bracket holding on our driving lights with an attractive pod for our massive, new PIAA fog and driving lights. The pod keeps the lights out of harm’s way, locates them out of the cooling air for the engine and can be quickly removed or installed for daytime and night stages. It also reduces vibration, which can be distracting.

We fitted 15 inch DP Enduro wheels shod with Michelin rally tires. Our competition tires are size 14/62-15 L4, meaning they are 140mm wide, 62cm overall height and 15 inches in diameter using compound No. 4 on an L-shaped block tread design. With four-wheel-drive cars, particularly those with locked differentials, it’s important to use the same size tires on all four corners. Otherwise the drive train will fight itself, possibly leading to an expensive repair. While rally tires may look like snow tires, they are really very sophisticated and provide surprising grip on pavement and are nothing short of phenomenal on dirt. The extremely strong sidewall construction of the Michelins makes them incredibly resistant to punctures from sharp rocks.

We try to start an SCCA National PRO Rally with six new tires. In 12 events, we’ve had only two punctures (both on the same stage!) and usually finish an event with four serviceable tires and two new spares, all of which can be used for the next event. This provides us with a complete set of spares in case the event is particularly brutal on tires. To be totally prepared, we should have gone to Michigan with ten new rally tires, six snow tires and six Showroom Stock tires for the tarmac stages. But we couldn’t afford to be totally prepared and, in the end, that was okay.

Halfway through the first season I asked MFI Power in Garden Grove, Calif, to rebuild the engine. John Mueller focused on a broad powerband with strong low-end torque rather than maximum horsepower. With the stock gearing, we had often found ourselves lugging out of sandy, uphill corners at the bottom of second or third gear.

For the most part, Mueller rebuilt the engine to stock specifications, porting and polishing where possible. However, he lightened the crankshaft by five pounds and dropped another nine pounds off the clutch and flywheel assembly to maximize off boost performance. He knife-edged the crank and machined the flywheel from aluminum stock. We added Torco 5W30 synthetic racing oil to provide maximum protection and minimum friction. We think Torco might have saved the engine when we lost all the oil in Michigan.

The result was an estimated 190 horsepower compared with 135 hp stock. We selected a Centerforce competition clutch and pressure plate designed for an RX-7 to handle the increased horsepower and the abuse of rallying. Road/Race designed a pair of hood ducts to extract hot air from the engine compartment. These reduced engine temperatures at the hot weather events, and we could see the hot airwaves coming out of the engine while waiting for the start of stages.

Our most exotic piece of equipment, a close ratio competition gearbox, was installed late this past season. Our top speed has dropped to somewhere in the 90s, but the gearing has really paid off

Competing for an SCCA National PRO Rally championship is not cheap and should not be considered a grassroots motorsport any more than IMSA Firestone Firehawk is grassroots road racing. However, it is possible to run a Divisional series or selected National events on a budget. For my money, there’s not a more exciting or fascinating form of the sport available.

When he’s not racing in PRO Rallies, Mitch McCullough is involved in motorsports public relations for various companies.