SCC Magazine Project Eclipse – Final

Mitsubishi Eclipse GSX Part Six

Time To Say Goodbye

By Kieth Buglewicz

Reprinted with Permission

It’s not like we didn’t know it was going to happen, It never really belonged to us, despite how close we had gotten to the car. No, our long-term Mitsubishi Eclipse was ultimately, a short timer. But in the year (plus 3 months, thanks to Mitsubishi’s benevolent PR king Kim Custer) we had the car, we had more fun than is probably legal, were able to cram a good amount of performance under the hood, and discovered at the end that it, indeed, all work as advertised.

This speaks volumes for the versatility and flexibility of Mitsubishi’s 2.0 liter turbocharged four cylinder. But despite our efforts, we could have done more. The brakes were still stock. The engine itself had never been opened, so there was room for porting and polishing. The car desperately needed an upgraded intercooler. The list goes on practically forever, and you can see what else we would have done if we could have kept the car longer by checking out Dave Coleman’s sidebar.

Rather than express a wish list, I’m here to recap what we have done, and try to keep emotion out of it.

We got the Eclipse in May of 1997 with a scant 26 miles on it. It was, however, a case of the third time being charmed, as we had gone through two other cars previously. Our first car was virtually identical (it had a brown interior) and was pulled from Mitsubishi’s press pool. However, after a week with the car, an ugly problem reared its head: The transmission was making horrendous gronking sounds in first gear at full throttle. We returned the car, and were told it was actually a pre-production vehicle that had already had the transmission replaced. We were asked if we would like a brand-new car built especially for us at Mitsubishi’s Normal, 111. plant. Not being stupid, we said yes.

After a week . . . The transmission was making horrendous gronking sounds in first gear at full throttle.

The second car we never actually saw. After about a month of waiting (not unusual for a special order), it showed up in April. We got the call from Steve Kosowski (also of Mitsubishi PR) that our new baby was delivered…but there was another problem. Somewhere, somehow, despite the fact that Steve wrote on the order form that we wanted a five-speed manual transmission (he showed us the form), the car arrived with an automatic. Crap.

Since, as everyone knows, an automatic transmission in a car like the Eclipse would be just as useful as training wheels, we agreed with Steve’s suggestion that the plant build us another car. One month later, it arrived. Steve told us it wasn’t quite to spec either, as it had a gray interior rather than a brown and black one. Gray, brown, black, lavender…as long as all the big mechanical bits were in place, we were happy.

It didn’t take long for us to break in the car After an oil change at 500 miles, and another at 1,000, we were ready to play. One thing had become apparent to us almost immediately: If we had looked at the order form more carefully, we would have skipped the sunroof. This is advice anyone over about 5 feet 11 inches tall should take to heart. The seating position was also uncomfortable for tall people because of the low slung steering wheel. Even at its uppermost adjustment, it was in the way Incidentally, aside from amputees, I can’t imagine who would set the wheel at its lowest setting; the wheel almost completely blocks access to the pedals.

Despite having to adjust ourselves to sit in the car, we were impressed by its power and grip. But the break-in period also allowed us to determine our first course of action. One of the first things that drew attention to itself was the suspension. The Eclipse is no light weight ours weighed in at more than 3,500 lbs with two people on board but its strong motor makes up for it by yanking the car around at a good clip. The suspension is stiff enough to stick the car in a turn, but soft enough to let the heavy body gently bob up and down on fast sweepers. You never feel like the car is going to fly out of control, but the feeling is a little unsettling. We decided to upgrade not just the springs, but the shocks as well to give us the handling we wanted. We opted for Eibach’s Pro Kit springs along with Koni’s s adjustable shocks.

Not only did the suspension mods work, but the incremental lowering job (only about an inch all around) hunkered the car closer to the ground, making it look like a badger: Low, wide, and always angry about something. Naturally, the suspension mods made the car much more capable than its stock tires (lackluster Goodyears) could handle. So we upgraded to 225/40ZR18 Dunlop SP9000 tires. They proved to be a good choice, with very good dry grip and virtually untouchable wet grip. Coupled with the all-wheel drive character of the Eclipse, this was one sports car that was unafraid of the rain.

The second thing we noticed about the car in its stock form was that after an initial surge of boost, power would start to fall off at about 5500 rpm. Frankly, revving the engine to its 7000 rpm redline was fruitless: The engine only produced noise after about 6200 rpm One glance at the engine bay and it was clear the anemic stock intake and exhaust were to blame. We installed a HKS cat-back exhaust system, which produced the expected exhaust note for an Eclipse: A loud farting blat. On the intake side, we installed a K&N intake, a GReddy blow-off valve, and a Road/Race Engineering intercooler pipe.

Mike Welch at Road/Race is well known in the Eclipse community as a guy who seems to have an unhealthy amount of knowledge about these cars. If he could, I’m sure he’d sleep with one under his pillow. But that knowledge made him our unofficial Project Eclipse Performance Guru, and we turned to him for just about every question we wanted answered. Opening up the intake was his first suggestion, and he let us in on a secret that is often overlooked. The stock blow-off valve feeds back into the intake pipe. This keeps the computer happy, since it has already measured that air with the air mass sensor. To keep noise levels down though, the blow off valve dumps into a four-inch long dump pipe that extends far down into the intake hose.

Not only did the suspension mods work, but the lowering job (only about an inch all around) hunkered the car closer to the ground, making it look low, wide, and always angry

What this means is that although the intake pipe looks big from outside, it is significantly blocked by the dump pipe. Mike’s solution to this intake blockage is simple: Cut the return pipe out. It doesn’t actually make a lot of power, but it adds to the responsiveness of the engine. The gains were immediately apparent. The car built boost much more quickly and held it much longer, making power almost all the way to redline.

Mike’s solution to this intake blockage is simple: Cut the return pipe out. It doesn’t actually make a lot of power, but it adds to the responsiveness of the engine

Making performance modifications to our car presented us with the problem of quantification. We needed to demonstrate that our Eclipse felt faster because it was, not because we could hear the whoosh of the turbo and the flatulent exhaust note more clearly after our mods. Luckily, we had a solution to getting “dyno” results from our Eclipse in the form of our Vericom 2000 performance computer.

In an oversimplification, the Vericom is essentially an accelerometer. By measuring how quickly a car accelerates in a certain gear, then plugging in weight, ambient air temperature and other factors, one can calculate how much power the car is making. The results were consistent enough for us to publish, as long as we tested back to back each time (the Vericom turned out significant fluctuations depending on air temperature). The result was a solid 30-hp increase for slightly less than $1,000 worth of parts that would be easy to install for even a mediocre mechanic.

Naturally, we wanted more power. So we decided to turn up the wick with more boost. This produced cries of “You’re gonna kill it!” from our photo editor, Les Bidrawn. Multiple assurances couldn’t dissuade him: He was certain we were about to murder our car.

Flush with our early success, we figured that just by wiring in an Apex boost controller and fuel computer, turning the boost up to about 17 psi and hitting the streets, we’d be flying fast. And we were right, to a certain extent. The boost controller fattened the midrange power significantly, but was unable to hold boost very long after about 5000 rpm. We had run up against another wall, although far earlier than we had anticipated. We turned to Road/Race for an answer.

The stock turbo, as it turns out, is barely adequate for the stock engine’s needs. Although the Eclipse is rated at a peak boost of 14 psi, it holds this only for a few hundred rpm before boost falls off to about 9 psi by redline. Part of the problem is with the crummy stock blow off valve, which has virtually no method of sealing against its seat, and has a spring so weak it can be pushed down with your pinkie. We replaced that in step one, but still had boost problems. We thought that by adding a boost controller, we would be able to hold boost to redline.

In the mean time, we had moved the Apex turbo timer, fuel computer and boost controller to the center console. Although the stock stereo sounded great, it was removed for our surgery. Replacing it was an Alpine three disc in-dash CD changer. The sound was great, and the unit was loaded with features. Competition Soundworks in Cerritos, Calif. did the installation work, and we undertook mounting the Apex gear under the Alpine unit ourselves. The result looked great, and was much more ergonomic.

The next step in our upgrade was the most drastic. Most Honda and Acura drivers would suggest the very popular T3/T4 hybrid turbo. However, that particular turbo requires significant heat shielding to prevent it from melting the air conditioner fan. Instead, Turbonetics in Moorpark, Calif., set us up with an upgraded version of the stock turbo. Since we were only planning to run about 18 psi of boost, the modified stock turbo would be more than adequate. We also had a couple other concerns, mainly that the car was driven daily, and we wanted a turbo that would give us the power we wanted without excessive lag. We also wanted something that would be reliable, for the same reason. Longevity was the key, and since the car did eventually have to go back to Mitsubishi, we wanted to return a working automobile, not a car-shaped pile of non-working parts.

Turbonetics modified the turbine and compressor housing of a stock Eclipse turbo to accommodate larger wheels. This in turn allowed the turbo to flow more than 30 percent more air without significantly increasing lag, an advantage we probably would not have had if we went to a physically larger unit. We once again turned to Road/Race Engineering for installation, where Mike had a suggestion for improving flow. A ported exhaust manifold, he said, would significantly aid flow to the turbine, as would porting the huge cast iron exhaust flange from the turbo to the exhaust down pipe. The result was much snappier throttle response, gobs of midrange power, and virtually no lag whatsoever.

But the high end was still falling off boost, regardless of the new turbo. One culprit we thought might be to blame was the fuel system. After we installed the turbo, the fuel cutout would abruptly shut off the fun in cool weather (when the intake charge was most dense). The car felt like it hit a wall each time it happened, and also made the check engine light come on for the first time (it also had us wondering if, after all, Les had been right). To cure the problem, we installed a set of 550 cc injectors from RC Engineering next, as well as a higher capacity fuel pump and exhaust gas temperature gauge to properly calibrate the Apex fuel computer. We also installed a 3inch stainless steel, mandrel bent downpipe from Hahn Racecraft and a 3-inch catalytic converter to remove the final obstructions from our exhaust system.

We once again succeeded in improving mid-range output, with another incremental gain at the high end. But at last, we found why top end power had been so elusive. While he was tuning the fuel compute; Mike Welch noticed that as he data-logged speed and rpm, the two would increase at the same rate (as they should) through the middle of the rev range, but at high rpm the engine would start accelerating faster than the car! There was only one answer: The stock clutch was being overwhelmed at high engine speeds when the turbo was at full song. The fix came in the form of a three-puck Exedy clutch.

Flush with our early success, we figured that just by with In an Apex boost controller and fuel computer, turning the boost up to about 17 psi and hit the streets, we’d be flying fast. And we were right, to a certain extent

Man, did it work. Finally, the top end acceleration matched the low- and mid-range surge. The engine held boost now to redline, and the car felt like we had installed an afterburner instead of a clutch. No sooner was the clutch installed than we took the car to the Streets of Willow at Willow Springs Raceway in Rosamond, Calif., for a little testing. The new clutch demanded respect, requiring good matching of revs at every shift to avoid a lurch when the clutch grabbed…and grabbed hard. But driven even moderately well, the Eclipse screamed around the track. Far from lithe and nimble, the GSX felt like it made its way around the track by getting the pavement in a death grip and bullying its way through the laws of physics. Driven full bore, the Eclipse could dive into each corner with the ABS pulsing like mad, fight its way to the apex, and then spit the corner out behind under full boost. Powering out of the corner was always the most difficult part, as terminal understeer was often the result when a surge of boost felt like it was lifting the front wheels and pushing them sideways. Extreme understeer would make the out side front tire chatter across the pavement a very unsettling feeling but if you balanced steering input correctly on the exit, the Eclipse was extremely fast. Of course, all this brute force did take its toll on the brakes and tires, but it sure was fun!

Far from lithe and nimble, the GSX felt like it made its way around the track by getting the pavement in a death grip and bullying its way through the laws of Physics

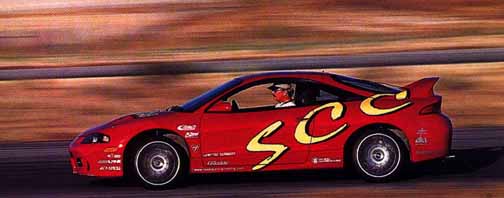

Which more or less brings us to where we are today, returning the car to Mitsubishi. During its time with us. The Eclipse appeared at numerous event, including the 1997 SEMA show in Las Vegas, the 1998 SEMA Import Auto Salon and the 1998 Long Beach Grand Prix. Not to mention the numerous local drag races and car shows. With its wild graphics scheme (courtesy of Imagine It Graphics), the Eclipse excelled at attracting attention. Which, of course, was sort of the whole point.

So, we bid farewell to the Eclipse, impressed with its performance potential and with the fact that nothing ever broke, despite everything we threw at it (a worn clutch doesn’t count). What the future holds for Mitsubishi’s sporty coupe is truly unknown at this time. We’ve heard rumors that the turbocharged 2.0-liter motor will disappear with this particular model, replaced by the new 3.0-liter V6 found in the ’99 Galant. With 195 horsepower, this would not necessarily be a bad thing. On the other hand, we’ve also heard that the turbo motor may make a return. You can expect all wheel drive to bid a final farewell: Mitsubishi sells very few turbocharged models, and even fewer GSXs.

| What it Cost | |

| Suspension | |

| Springs: Eibach Pro Kit | $225 |

| Shocks: Koni | $576 (set of 4) |

| Wheels: Kosei Seneca 18 x 8 in. | $420 (each) |

| Tires: Dunlop SP9000 225/40ZR18 | $228 (each Tire Rack Price) |

| Engine | |

| Exhaust: HKS | $480 |

| Turbocharger Turbonetics T28 upgrade | $850 |

| Intercooler Pipe: Road///Race | S90 |

| Blow-Off Valve: GReddy Type S | $205 |

| Intake: K&N | $95 |

| Fuel Computer: Apex Super AFC | $369 |

| Turbo Timer: Apex | $99 |

| Boost Controller: Apex | $579 |

| Sound System: | |

| 3-disc in dash head unit: Alpine 3DE-7886 | $480 |

| Speakers: Alpine SPS-1326 | $80 |

| INTERIOR: | |

| Short Shifter: Pace Setter | $190 |

| Shift Knob: RAZO | $85 |

| Pedal Pads: RAZO | $77 |

| EGT Gage: Apex` | $211 |

| Boost Gage: Apex | $170 |