Edmunds Inside Line – GT30R Hearts AMS Widemouth

2008 Mitsubishi Evo GSR: GT30R Hearts AMS Widemouth At RRE

By Jason Kavanagh | September 16, 2009

Once the turbo, clutch and injectors were installed in Project Evo X, Mike Welch of Road Race Engineering got to work on the dyno.

Let it be known right now that to make real power on 91 octane, regardless of the hardware involved, is a royal pain the rear. Mike had his work cut out for him before he even began.

Oh, and Mike raised the crazy up one more level. He filled our tank with 91 octane from 7-11. It’s madness, yet there is method to it–if he can make our car knock-free on this utter crap fuel, then it’ll be safe on any fuel we’ll ever fill the tank with.

On to the tuning, then. First he scaled the bigger ID1000 injectors in the ECU and roughed in a conservative calibration. From there he gradually tuned the car, adjusting those scaling parameters, changing intake and exhaust cam timing, boost pressure and ignition timing.

During and between runs Mike monitors more than just output. There’s knock activity, fuel trims, air-fuel ratio, coolant temperature, intake temperature, intercooler effectiveness… you could say that a tuner’s job is like juggling cats next to a running chainsaw. If one cat gets away from you…

…ask him to switch off the chainsaw.

Eventually, the car stopped making power and started becoming knock-sensitive. That’s usually the point where you’re done and need to back off a bit to have a safe calibration.

The problem is that at this point, it just wasn’t making much more power than it was with the stock turbo. Everything looked good otherwise (and we have a nice closed-loop idle with the ID1000s; no nonlinearities, and a relaxed 62% duty cycle at redline).

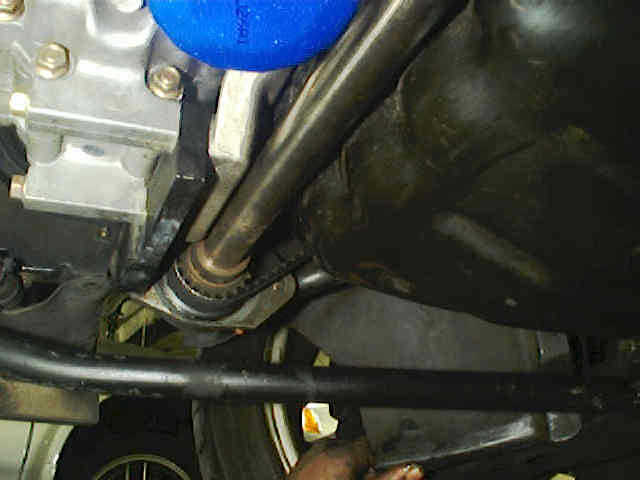

As for the power situation, long story short, our car still had the stock exhaust elbow and downpipe. And that was a problem.

This elbow is that part of the exhaust that connects the turbo’s turbine discharge to the cat. Stock, it’s a restrictive little thing. One theory is that Mitsubishi engineers had to make the elbow all kinked up to accomodate right hand-drive cars. Basically, to keep it away from the steering shaft that pokes down in that same region.

Whatever, the operating theory is that the stock downpipe was very likely choking off flow and introducing backpressure. To address this, AMS sent us a higher-flowing replacement they call a Widemouth Downpipe. It’s an apt name. Comparison between the AMS Widemouth and stock piece can be seen below. You could drop a baseball in one end and of the Widemouth it would drop out the other.

It beautifully made, too, comprising cast stainless segments with a generously-sized flex section to replace the stock spring/bolt arrangement.

Back on the dyno with the new downpipe–RRE mentioned that installing the Widemouth was a bit tricky due to the physically larger GT30R–Mike noticed an immediate benefit. The car was now less detonation-prone, so he was able to better exploit the higher-flowing nature of the GT30R. From about 4200 rpm to redline, the Widemouth allowed him to tune in an additional 25 hp… and that’s with running a bit less boost in the midrange, too.

So the lesson here is that matching components is critical when we’re talking about the kind of output this 2.0-liter engine is making while being fed The Worst Fuel On Earth.

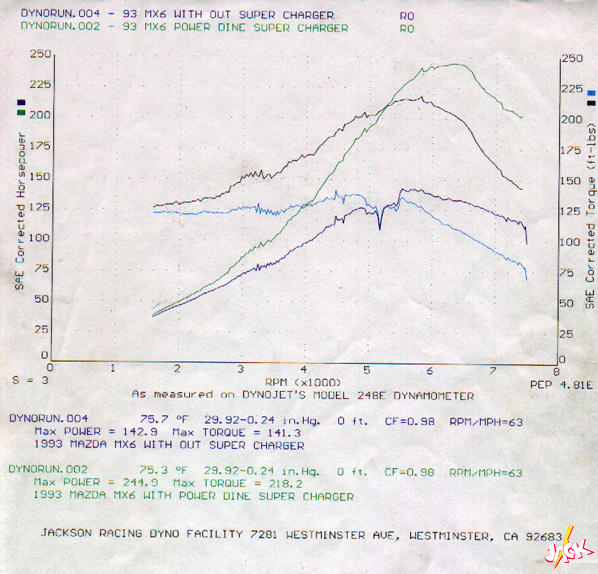

This post is getting long-winded so I’ll post up a dyno chart of its final state of tune in a followup blog entry.

Jason Kavanagh, Engineering Editor @ 25,000 miles.

EDMUND’S Project EVO Part III – Dyno Tuning

2008 Mitsubishi Evo GSR: Tuning at Road Race Engineering

Edmund’s Inside Line – Road Race Engineering Knows Evos

From EDMUND’S Inside Line

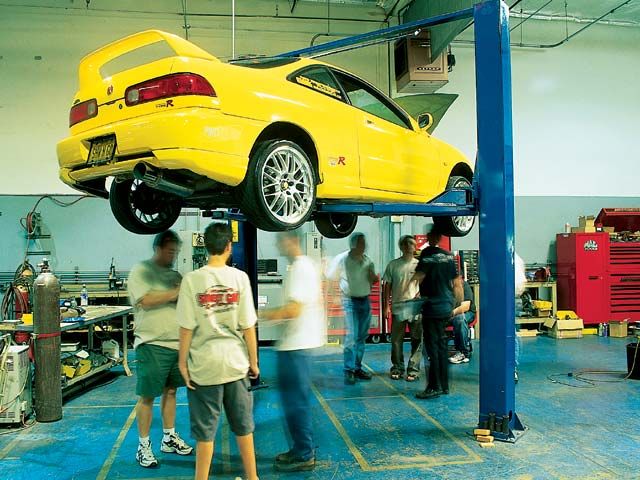

I think we picked the right place to have our Long-Term 2008 Evo GSR worked on. The Cosworth cam install is happening just off-camera to the left here in Road Race Engineering’s garage, and there are still more Mitsubishis to the right .

And then there’s the parking lot outside…

Just be careful where you park:

by Jason Kavanagh, Engineering Editor @ 15,851 miles.

Edmunds Inside Line – GT30 Tuning

2008 Mitsubishi Evo GSR: RRE Tunes The Garrett GT30R

By Jason Kavanagh | September 17, 2009

Some tuners use ECUFlash. Others swear by EcuTek. Mike Welch of Road Race Engineering, on the other hand, doesn’t play favorites.

While Project Evo X, our long-term 2008 Mitsubishi GSR, was in his care, Mike constantly switched between the two calibration interfaces while on the dyno. It turns out that certain functionality and datalogging can only be accessed through the EcuTek interface, while other tables are better served by ECUFlash. An ECUtek license costs real money, though, and uploading changes to the ROM takes several minutes instead of seconds. So he uses both. These are the tricks you learn when you’ve been modifying Mitsubishis since 1994.

After adjusting the calibration on the dyno until he was satisifed it was producing safe and consistent power, checking the vitals on the street and making subtle tweaks, he was done tuning Project Evo X with the Garrett GT30R turbo.

The rest of the story and Dyno Charts on Edmunds blog

RRE At Your Local Library

WINTER TIME!!

Cozy up to the fire in the cold California heat with a good book!!

http://www.amazon.com/Mitsubishi-Diamond-Performance-TuningHP1496-Hands/dp/155788496X/ref=pd_sim_b_3

EDMUND’S Project EVO X [Part 1]

To find out just how much power Project Evo, our Long-Term 2008 Evo GSR, currently generates, we went to someone who knows these cars.

To find out just how much power Project Evo, our Long-Term 2008 Evo GSR, currently generates, we went to someone who knows these cars.

Road Race Engineering has been working on Evos since before they were sold in the USA. And they’ve been building, racing, tuning, modifying and repairing 4G63s since 1994. You could say they know a thing or two hundred about how to make Mitsubishis go fast.

In Road Race Engineering’s huge 6,000 square foot facility in Santa Fe Springs, CA, they got to work. Project Evo’s wheels came off and the four Dynapack hub dynos were carefully bolted on.

Then we fired the engine, warmed it up to operating temperature by “driving” at light load and did a few pulls.

Now, before we go any further, it’s important to remember that not all dynos are created equal. Comparing results from different dynos is a fruitless and deceptive exercise. Even if you test the same car on two different dynos on the same day, the results can be all over the map.

In fact, we’ve already done that exercise with a GT-R.

Since you just clicked that link and re-read the test, you know only to compare results from Road Race Engineering’s Dynapack dyno to other runs made on that dyno. A dyno is a tuning tool, not a manhood-measuring device. Focus on the gains rather than the absolute numbers.

Whew, okay. Back to Project Evo’s baselining exercise.

We did four or five pulls and the peak numbers were about 320 lb-ft and 325 horsepower. I say “about” because the run-to-run variation floated a few hp or lb-ft higher or lower than these values. I’ll post a representative dyno chart once my latptop starts cooperating.

Mike Welch, owner of Road Race Engineering, says that bone-stock Evo Xs typically generate about 250 horsepower on this dyno.

Factor in your favorite guesstimate for drivetrain loss based on all of this and we can see that we’re roughly 65 horsepower shy of our power goal for Project Evo.

So, now what? With a decent complement of bolt-ons, the next logical step is cams. We talked with our friends at Cosworth in Torrance and they handed us a set of Cosworth MX1 cams, which Road Race Engineering graciously volunteered to install and re-tune for.

More to come.

Jason Kavanagh, Engineering Editor @ 15,851 miles.*

*we drove two miles on the dyno.

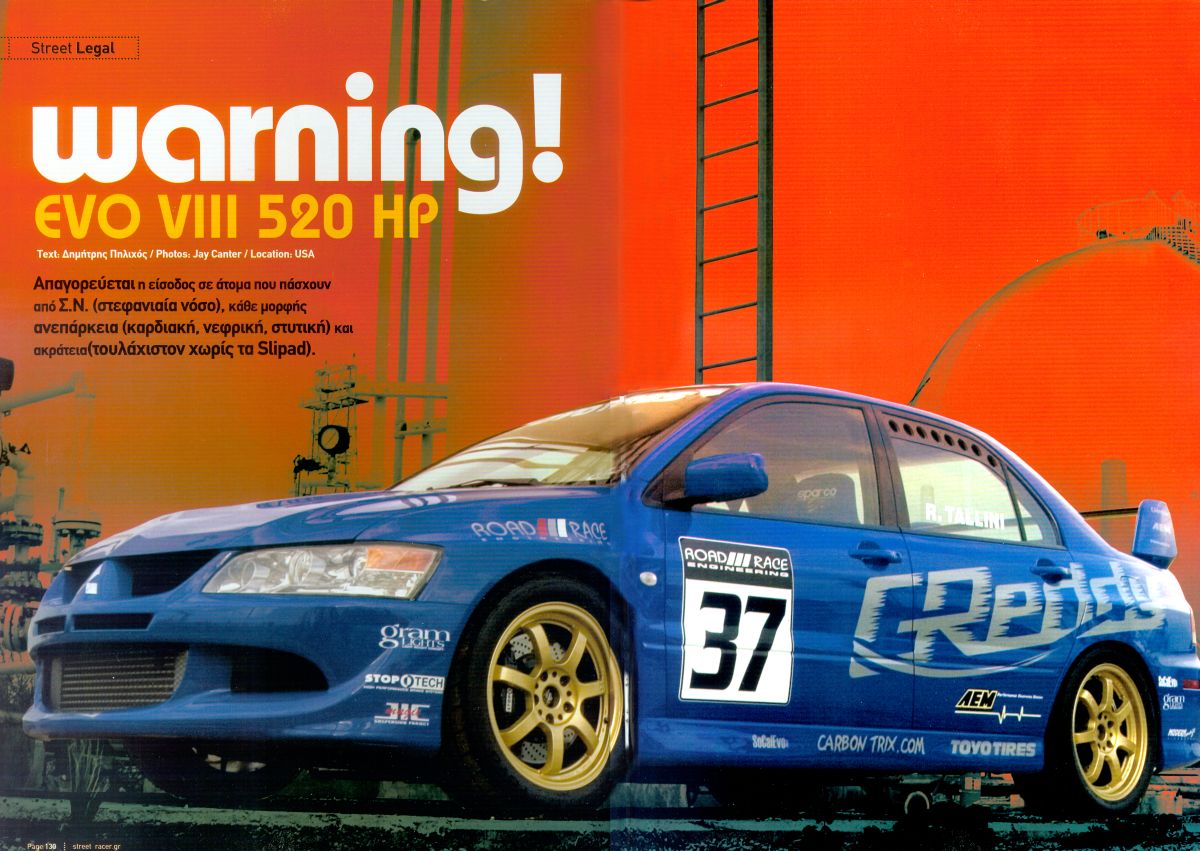

Russ Taylor EVO 8 – Schooled Magazine

From Schooled Magazine September-October 2008 Issue

Over the next few issues, Schooled Magazine and Road Race Engineering (RRE) will take a stock 2008 Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution X and perform some serious modifications to show you what you can do to enhance your vehicle. This issue I hung out with the RRE crew as they modified the performance of the vehicle. By Russ Taylor

Intake Challenge

When choosing an intake system it is important to consider airflow. The more airflow the engine receives the better it will run. To find the best intake system for the Evo X, we wanted to compare three different systems to see what would give the best gain. With the three systems-the stock intake, Injen Cold Air and AEM Cold Air Intake- Schooled headed to Road Race Engineering (RRE) located in Santa Fe Springs, California to get the dyno results on which system would give the best performance gains. The dyno is a system that measures horsepower (WHP) of the vehicle.

I met up with Mike Welch, the master tuner at RRE, who has been tuning Mitsubishi vehicles for over 12 years. He was the perfect person to handle the intake challenge for the Evo X. We started with the dyno run to find the base numbers to compare against. The dyno placed 248 WHP with no modifications done to the vehicle with the stock intake system installed. Now that we had a baseline to judge by, we were then able to compare the two intake systems.

We started with the Injen (www.injen.com), and the results were depressing. There was only a 2 WHP gain. Considering that the unit retails at over $400, this was definitely not a very good bang for the buck.

We then tried the AEM intake (www.aempower.com) which increased the vehicle with a power gain of 26 WHP. With the cost of the intake at $285, this was a huge gain for a low price. AEM’s engineers took a different approach and designed a power-producing enclosed airbox. The airbox is constructed from cross-linked polythene. AEM’s revolutionary DRYFLOW synthetic performance air filter is the first cleanable, reusable performance air filter that does not require oiling to filter and trap dirt.

Even though the Injen unit looks considerably nicer with polished pipes than the AEM intake, the 26 WHP gains made our choice obvious- to go with AEM for the project.

Custom Fabricated Exhaust by RRE

To help with the airflow for the vehicle, RRE made a custom fabricated exhaust system. Art Thavilyaei, one of the RRE crew, pieced together what later would become a custom fabricated dual exhaust system.

RRE decided to use 3” piping going into dual 2.5” piping for the rear section, and the process was amazing to watch. They start by removing the stock exhaust system. A jig is used to hold the new piping in place as measurements are taken and airflow is considered. Once each piece is measured, it is then cut, ground, and welded in place with the use of the jig. Each bend and weld in the exhaust system potentially decreases the amount of airflow from the engine. Art took his time to ensure that the end product would produce the greatest amount of airflow from the vehicle.

After several labor-intensive hours, Art finished with the placement of the exhaust system only to have to remove the entire exhaust to perform the finishing welds. He completed the welds to perfection, and he placed the finished exhaust on the EVO X. Mike ran the car on the dyno and saw a 17 WHP gain over the stock exhaust. The total cost for the exhaust system like this from RRE is $650. It gives the vehicle solid power gains and sounds a lot nicer.

With the AEM Cold Air Intake and the custom fabricated exhaust by RRE, we saw a total 45 WHP increase on the vehicle. “The best bang for the buck is the intake and exhaust,” says Mike. With a total of 45 WHP gain, Schooled Magazine would have to agree.

In the next issue Mike will perform a custom tune and will add some additional performance parts to get the most gains possible out of the Evo X. You don’t want to miss the next issue of Schooled!

RRE EVO – Import Tuner Magazine

Nine Lives – 2003 Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution VIII

Not all Lancer Evolution VIIIs made it into public driveways. Some were destined for other fates, the most common of which being something we journalists know intimately as “press car” status. In most cases, press cars are destined to be crushed after their short test phase, because they are released before seeing approval from the Department of Transportation and the EPA. It sounds like a sad story, but really you’d be hard pressed to find a rental car as abused as most press cars are.

Think about it. These things are driven by hundreds of different people for one week at a time, with no concern whatsoever for break-in miles, warm-up time or anything else of the kind. If you think the Evo on these pages has ever slowed for a speed bump or been rubbed with a diaper, you are sorely mistaken. Press cars age in dog years. A press car with 20,000 miles on it is already gone. That’s not to mention that this particular press car started life in rainy mainland Malaysia and went on to a career in racing before evolving into the wide-body race car you see before you.

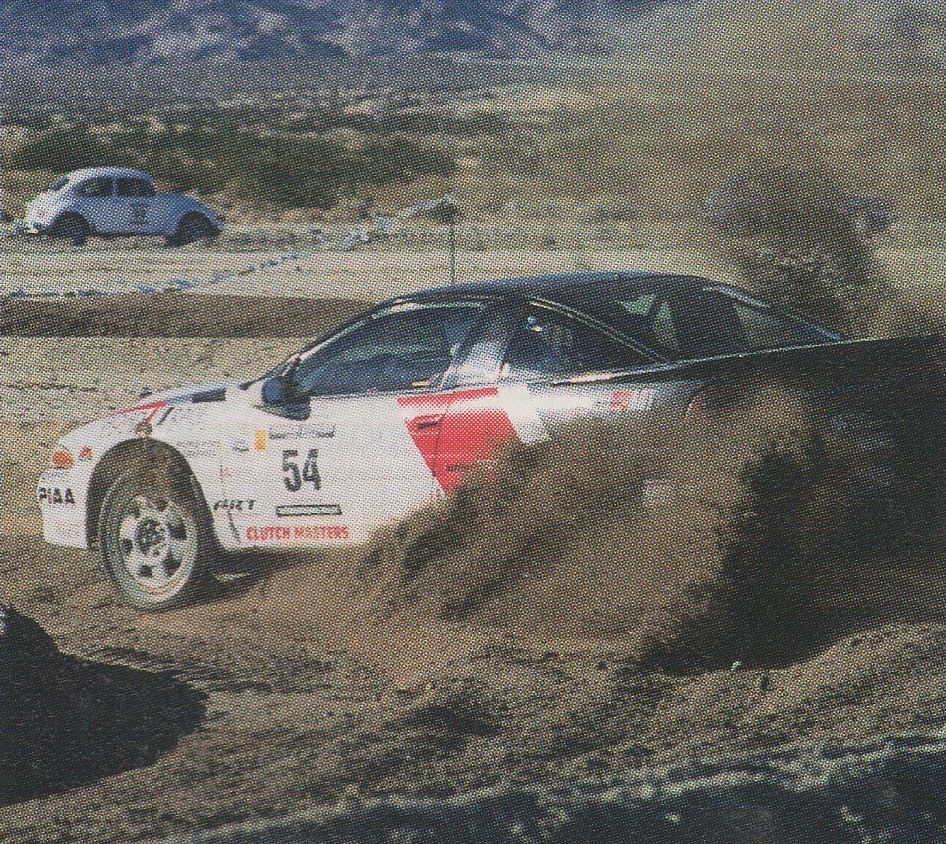

So you’re looking at an anomaly-the press car that just won’t die. Not because it hasn’t wanted to a few times in its life, but because it’s had too many Dr. Frankenstein owners force it back to life when all it wanted to do was call its long career in. In the hands if its current owners, Road Race Engineering (RRE) in Santa Fe Springs, Calif., it won’t be facing its demise in the jaws of a metal junkyard monster any time soon. According to RRE’s Mike Welch, “We don’t get rid of cars, we race them until they reach the end of their life cycle, then we own them some more.”

This Evo VIII started life at RRE as a race car back in 2003. This isn’t your typical story of a car that started small and moved on to the big modifications. The car had barely been in the RRE garage for a week before stock parts were torn off. The stock turbo was ditched in favor of a GReddy turbo kit and front-mount intercooler, while the factory suspension was tossed and replaced by a system from JIC. A four-wheel big brake kit from Stoptech with four pistons on each caliper and 355mm rotors all around got the party started right. Finally, a custom sheetmetal intake manifold from Magnus helped to increase airflow into the engine.

But as the American Evo aftermarket developed, Road Race Engineering was afforded a larger list of specialized components from which to choose. In addition, RRE developed many custom parts itself, like a cast turbo manifold-less prone to breakage than a tubular unit. The GReddy wastegate was exchanged in favor of an external unit from TiAL, while the GReddy Type-S blow-off valve was left to vent into the atmosphere. Intercooler piping leading to the GReddy core was replaced with a custom set from RRE. While Road Race was fabricating, it belted out a custom downpipe to guide hot air out of the turbocharger and into a Magnaflow exhaust. Being as inventive as the guys at RRE are, a Subaru up-pipe was used on the other side of the turbocharger and a custom intake was quickly fabbed up.

The turbocharger would be blowing boost into a 2.4-liter engine, machined out by Millenium Motorsports in Temecula, Calif. Before the new block was bolted to a Cosworth head, forged Wiseco 9:1 pistons were installed on top of forged Eagle H-Beam rods to keep the bottom end from turning into a boiler room for hot metal projectiles. The rods were then fastened around a balanced and counter-weighted crankshaft using ARP rod bolts.

The aforementioned Cosworth head seems to be the hands-down choice for all who race Evos. Maybe that’s because the only work teams have to do is unwrap the cellophane, bolt it on and race. It comes with a 272-degree camshaft for both the intake and exhaust sides of the valvetrain, stainless steel polished and oversized valves and polished combustion chambers. The valves stay seated with proprietary valve springs and retainers. Finally, a pair of cam gears from AEM was added to regulate valve timing events. Cosworth also clearanced the stock oil pan and a Setrab oil cooler was installed to keep temperature down during long race days in the California desert.

To keep the race car reliably fueled, RRE turned not to the aftermarket but to a car that has been on race tracks since the ’60s in some form or another, the Porsche 911. In this case, the Evo employs a Bosch external pump from the vaunted 930 Turbo in conjunction with a Denso internal pump, which in tandem provide fuel to a set of RC Engineering 1000cc/min injectors.

Since this Evo was built before the days of the American Evo RS, it was absent a limited-slip differential up front. RRE remedied the loss by installing a locking LSD from Quaife. To ensure all the power made it to all three differentials, a clutch and lightweight flywheel from Quartermaster were used.

Peak Performance of Lake Forest, Calif., teamed with Advanced Suspension Technology (AST) to provide a set of competition coilovers, while RRE teamed up with Progress Suspension to create the kind of anti-roll bars an all-wheel drive car equipped with copious amounts of rubber would need to rotate on the track. The rear bar measures 27mm in diameter.

The massive rubber comes in the form of 335/30/18 Toyo Proxes, wrapped around gargantuan 18×10.5 Enkei NT03+M wheels. Because of the APR wide-body kit, the wheels have a 25mm offset, something otherwise uncharacteristic of cars coming from the island of Japan.

Inside, Racetech carbon-kevlar seats occupy an otherwise lonely cockpit-stripped and roll cage equipped in-house by RRE. Carbontrix stepped in to add firewall and floor panels, but only because they serve a purpose on the racetrack. You might care about a good audio system, but the guys at Road Race couldn’t care less. To our “sound system components” question, they simply responded, “Magnaflow 3-inch exhaust, no interior.”

This thing was built to go fast, not impress the girl on roller skates at your local Sonic. And go fast it does-driver Robert Tallini has already taken home the gold at the ’04 FIA Mexican Championship (Open Class) as well as the Redline Time Attack in Fontana, Calif., (Overall Winner). If there’s such a thing as a car having nine lives, this one wrote the book. It’s been rebuilt more times than we can count and it’s attended SEMA as many years as the Evo has been alive in the states. Thanks to Road Race, it doesn’t look like it will be disappearing off the scene any time soon, either.

Whopsssssshhhhh!! RRE Shop EVO 8 gets famous in Greece’s “Street Racer” Magazine!!

Street Racer magazine sent Jay Canter to the shop a couple months ago to get some pics of our shop EVO 8 race car. It just came out in their August issue! We went to the closed refinery down the street and took some beauty shots and also ran the car through Turnbull Canyon for some driving shots. Here is how it turned out. What’s it say about the car? Who knows. It is Greek to me :-P. -Mike W.

If any Greek readers out there can translate this for us, a prize will be awarded. Meanwhile, I have done my best to translate through using my otherwise useless Philosophy degree. -James Singer

[click on these smaller images to GO BIG!] (more…)

Toxic Photoshoot! RRE EVO 8 Race Car gets shot!

A Euro magazine sent Jay Canter to the shop recently to get some pics of our shop EVO 8 race car. We went to the closed refinery down Lakeland Rd asked if we could get in to take some pics with the freaky background. With a little begging and a lot of convincing that we wouldnt be doing donuts and generally causing a hazmat response – we got in. After we took some beauty shots, we ran the car through Turnbull Canyon for some driving shots with the car moving.

Looking forward to see how it turns out. I can shoot over the shoulder of these pro photographers all I want and… well with them being professionals and all, my pics look amateur for some reason :-P

Here are my point and shoot pics:

Sport Compact Car Magazine – The Ultimate Streetcar Challenge 2003 : The Guru Panel

Reprinted with permission from Sport Compact Car, June 2003

Our assembled panel of automotive know-it-alls consisted of three aftermarket powerhouses: John Concialdi of AEM, Oscar Jackson of Jackson Racing, and Mike Welch of Road Race Engineering; and two engineers: Dan Ehrlich of The Aerospace Company, and Mike Kent of Bell-Everman, Inc.

The incessant buzz of a defective overhead light, which rang through their heads the entire day, would have driven any sane person mad, but engineers have an almost inhuman endurance in the face of tedium and monotony. Anyone else would have taken out their frustration on the last few cars with crushing scores and harsh criticism. The last car that passed by our panel actually won.

Judging was focused on six areas of the car, each with a different number of points available, reflecting that area’s importance for performance. The engine was worth 40 points, the drivetrain 15, the suspension 20, bodywork was worth only 5, and brakes and interior modifications were worth 10 points each. The judges focused on modifications, looking for logical changes focused on improving performance. The fact that the Laminar Viking was built from scratch, essentially making it one giant modification, was surely crucial in overcoming the judges’ days’-end grogginess.

The Laminar’s turbocharged rotary wowed the judges, as did the Penske shocks and, of course, the featherweight tube frame clothed in carbon fiber. The judges were disappointed only with the rotary’s oil leaks and the exposed terminals on the fuel pump, which they deemed far too likely to start a fire should the Viking be rear-ended. But really, who can argue with 1,700 pounds and 360 hp? Mike Welch’s evaluation was, as usual, straight to the point. “He built the whole damn car from scratch and did it well. He wins.”

Paul Mumford’s Viper was only three points behind the custom-built featherweight. Credit the fact that it was built for the track by people who really know what that means. Penske shocks are a sure way to get the full 20 suspension points, and the Caldwell engine is a no-brainer for a high engine score, but it was the details that really impressed our weary judges. Details like carbon-fiber brake ducts, small air deflectors ahead of the front wheels, and the fact that the cold air duct in the hood was blocked off because the stock duct doesn’t actually work at speed. The wear and tear of countless track days, like the massive StopTech brakes that had clearly been cooked, also gave our panel a tantalizing glimpse of the outside world they’d been longing for all day.

Looking farther down on the finishing order tells you just how picky our judges can be. Deric Massie’s 384-hp Integra Type R was tagged by several judges for the fuel pump wiring. Too small a wire gauge, they said. Poor installation of the bolt-in roll bar and harnesses also drew the wrath of the geeks, leaving the Type R with a negative interior score from several judges. In fact, the Type R’s interior was deemed unsafe for our track tests, so the generous folk at Sparco stepped up and gave Massie new seats and belts so he could continue with the competition. The Type R’s engine, however, scored well. John Concialdi was especially fond of the AEM cam gears and fuel rail.

The Skyline’s eighth place finish seems odd, until you realize the car was mostly stock.

As good as a stock Skyline is, the judges were looking for modifications.

| RANK | CAR | POINTS | PEANUT GALLERY |

| 1 | Laminar SRX-7 | 100 | Who can argue with 1,700 lbs and 360 hp |

| 2 | Dodge Viper | 97 | Built for the track in every little detail |

| 3 | Toyota Supra | 92 | This car’s an engineer’s wet dream |

| 4 | Subaru WRX | 81 | Nearly show car execution on the engine |

| 5 | Mitsu Eclipse | 71 | You don’t make this much power without doing something right |

| 6 | Datsun 510 | 59 | Everyone loves 510s |

| 7 | Toyota MR2 | 52 | High concept, evidence of a rushed execution |

| 8 | Nissan Skyline | 40 | Good, but stock good |

| 9 | Acura Type R | 36 | Don’t use small wires in front of our judges |

| 10 | Mitsu 3000GT | 0 | Blue seats in a tan interior? Oh wait, engineering… |

Read more: http://www.modified.com/uscc/0303scc_uscc03/index.html#ixzz1WJWWli00

SCC Magazine – 2002 Ultimate Street Car Challenge: Mike’s on the Guru Panel

Sport Compact Car Magazine, March 2002

Reprinted with permission

There’s no quicker way to discredit your work than to show it to an engineer. Our panel of technical gurus consisted of Mitch Terry from AEM, Chris Weisberg from Magneson, Mike Welch from Road/Race Engineering and Jason Kavanaugh, a talented engineer who’s currently between jobs.

Our panel poked, prodded, admired and criticized the cars from every angle, evaluating the engine, drivetrain, suspension, brakes, body and interior for functionality and quality of execution. Then they came up with an overly complex scoring system that we won’t repeat here (because we don’t understand it) and rated them.

It was little surprise Tod Kaneko’s spotless Datsun 510 found itself at the top of the pile, but the number two finish of the Mustang raised eyebrows. Apparently the purposeful build-up of the Ford impressed our judges. Everything is focused on speed and reliability on the drag strip, with no effort wasted on frivolous modifications.

The Sentra scored a close third, thanks to its very sano turbo system and thorough performance-oriented approach to all the mods. Criticism from most of the judges focused on the disco paint job and the stock interior.

At the sad end of the score sheet was the largely unfinished and hideously complex MR2. Upon gazing unto the Toyota’s cramped engine bay, Mike Welch noted “For every cool part, something else is rigged, hacked, twisted or leaking.” These guys can be brutal.

The Hyundai, despite its massive performance, disappointed the panel. Most liked the concept, but the crude engine management, stock brakes and under-developed suspension offended their perfectionist sensibilities.

ENGINEERING JUDGING

RANK CAR POINTS NOTES

1 Datsun 510 100 Cleanest engine compartment in L.A.

2 Ford Mustang 84 Much improved on sucky dinosaur design

3 Nissan Sentra 83 Intentionally conservative

4 Acura Type R 82 Well thought-out engine mods Nissan 300ZX82Insane motor/heavy wheels

5 Nissan Skyline GT-R 79 Ghetto-flo test pipe

6 Toyota Supra 75 Too much power for stock brakes

7 Ferrari F360 71 Italian elegance/Japanese aroma

8 Toyota MR2 67 Rats nest

9 Hyundai Tiburon 64 High concept/low execution

Full article with links to all the tests hosted now on ModifiedMag.com:

Read more: http://www.modified.com/features/0203scc_streetcar_challenge_guru_panel/index.html#ixzz1hRXmjxl8

SCC Magazine – Ramada Express Rally 2000

Ramada Express Rally 2000

It’s a phrase no rallyist wants to utter.”Uh, Mike, can we borrow a hammer?”Mike Welch, of Road/Race Engineering, has along with his unhealthy fondness for fixing smashed rally cars, the world’s largest collection of rally car repair tools. Among them is The Hammer. The Hammer is a mangled, 60-LB block of lead impaled on the end of a Ford truck axle. We already knew The Hammer. We had seen it back at Road/Race’s shop and had even been known to pick it up just for fun, or point and giggle at the though of actually using a thing to fix a car. We weren’t laughing now.

Welch let us borrow The Hammer, but that was only the first hurdle. Next we had to swing it. The Hammer, when you count the handle and the various pieces of rally car shrapnel embedded in it, weighs at least half as much as the heftiest member of our Eyesore Racing Team.

Before long it seemed we had a carnival barker calling out, “Watch the big hammer swing the nerds!” A crowd had gathered to eye our vinyl topped shoebox of destruction with the mix of sympathy and humor appropriate for its current state. Bent, rally sore, and wheels akimbo, Project Rally Beater was coated with equal parts dirt, glory and despair. The despair was only getting thicker as, one after another, our 160-pound driver, 130-pound navigator, and 130-pound crew chief strained muscle and tendon to gently tap The Hammer against the rear wheel.

Then the crowd parted, and through the gap appeared Bob DeBenedetto. Spectator, rally nut, and easily 300 pounds of solid muscle, DeBenedetto probably could have bent our suspension back into shape with his hands. With a soft spoken “mind if I try?” he picked up the hammer lined it up with the top of the rear wheel and took a swing. The first hit was so hard the car jumped in the air. Dust gently wafted out of every crevice in the bodywork. But most importantly, the top of the wheel moved in about half an inch. He hit it again, and again, and again. “Hit it a little higher, a little farther forward, a little farther back.” With the precision of a laser alignment rack, The Hammer pointed the wheel back where it needed to go.

Back to Welch for another beg. With a welder borrowed from one team and a generator borrowed from another, Welch welded up the new crack in the control arm and that was it. With 10 minutes to spare, our rally was back on track and we were ready for the longest stage in American rallying.

The hammer incident was the culmination of a year’s worth of half-hearted preparation, corner-cutting and making do.

After noting the cheery disposition of a rally driver who had just tossed his car high into a pile of rocks at the 1999 Ramada Express Rally, it quickly became obvious that the true path to rally happiness was not through a WRX or Lancer, but through a Corolla, RX-7, or other suitably disposable beater.

Beaters can be flung against the rocks with wild abandon and then repaired for pennies–or replaced with another beater.

It was after watching this very rally in 1999 that we decided to build a beater ourselves. That we returned to the Ramada Express to race in 2000, however, was unexpected. The Beater’s first official competition was in the Treeline ClubRally, a local event so close to home that we didn’t need a trailer. At that point, the car was barely ready for competition, and the notion of being robust enough to finish a 46-mile rally was questionable at best. The 160-mile, three-day Laughlin event wasn’t even a consideration. But in the adrenaline of the moment, after most of the car proved somewhat durable (we did have a distributor failure that put us into last place for two stages) we gleefully proclaimed “We’re going to Laughlin!” Oh boy.

Of course, this event, officially dubbed the Ramada Express Hotel and Casino International Rally presented by Mitsubishi, is a much larger undertaking than Treeline. Treeline is six stages in one day, Laughlin is 15 stages in three days. Treeline is 47 stage miles, Laughlin is more than 160, with stage 11 alone totaling 45 miles. We had a car, now we needed serious logistics.

First lesson of rally logistics: Don’t make fun of your friends for driving trucks. When our longtime friend Jeff Payne traded in a Impreza 2.5 RS for an extended cab, four-wheel-drive Cummins turbo diesel pickup, we naturally unleashed the full force of our SUV hatred on him. Lucky for us, he has a short memory. You can fit a lot of rally car parts in the back of a Dodge truck, and the Cummins engine doesn’t even notice a rally beater on a trailer. Oh, and about that trailer. What’s an aspiring rally driver with limited parking supposed to do about trailers? We rented one from U-Haul for about $260 for five days.

And then there’s clutch paranoia. It isn’t a universal problem, but it strikes us before any long event. One Lap of America, 1999: Our WRX RA had been passed around to various members of the press for three years, and the clutch seemed to engage a little more softly than it should. Paranoid about a mid-race clutch failure, we talked Subaru into air freighting a new clutch from Japan and installing it one day before the car was shipped to the race. The old clutch, naturally, was less than half worn.

So it was with the Rally Beater. We had installed the engine only a few hundred miles before and the clutch, though worn, was far from ready for retirement. But somehow it suddenly didn’t seem to grab hard enough to give us confidence. A week before the rally, we frantically called Centerforce. Project Rally Beater has a clutch from a 2000 Datsun Roadster, an extremely rare car these days, but Centerforce not only makes a clutch for the Roadster, it was able to have it in our hands in less than two days! Now, that’s a pretty comprehensive product line! Working under a rally beater is an adventure in dirt. Removing the transmission after a rally means enduring an avalanche of gravel and mud every time you touch something, but in a few frantic hours, we had the old clutch out and the new one in. Naturally, the old one appeared to have plenty of life, but the two 30-foot black stripes on the street outside the office suggest the Centerforce is still far stronger.

And then there are the spare parts. At Treeline, we packed light. The only spare part was a distributor, which, as luck would have it, was the only part to break. For Laughlin, we packed everything. Digging around under shelves and behind workbenches revealed a treasure trove of forgotten parts. Spare engine mounts, brake drums, struts, steering linkages, alternators, starters, lights, hoses, fluids, anything and everything was put in plastic bins and labeled for the inevitable late-night repair sessions. Preparation for the rally was an all-consuming effort, mixing equal parts of paranoia and giddy excitement.

Naturally, the preparation didn’t end at getting the car to the event. We still had to unload it and pass tech. Normally, the pre-rally tech inspection is fairly minimal. The harnesses and roll cage were checked, the certification on your helmet and driving suits are reviewed and, because transit stages are often run on public roads, a basic check of headlights, horn, turn signals and brake lights is performed. No sweat, right?

Naturally, after 30 years of working perfectly, the brake lights chose to fail just as we were waved into the inspection. We got through (don’t ask how) and the preparation continued.

Word around the pits was that the first day’s forest stages were covered with snow and mud. Tomorrow was going to be a race of survival. Hmm, used, warm-weather rally tires, an open differential and snow. We stopped thinking about finishing well and started thinking about finishing at all. Five minutes before closing time, we came squealing into the last open auto parts store in town and bought tire chains. Is this an odd sport or what?

Then, we saw Rhys Millen preparing for the soggy mud/snow soup by cutting larger grooves in his nice, new Michelin rally tires. After a quick, tire-grooving tutorial from Millen, we borrowed a tire-gooving iron from fellow rallyist Paul Timmerman and started work on our tired, old Silverstones. Rallies have specific rules mandating when and where teams can work on their cars. In parc expose, teams may work on their cars as they are displayed to the public. However, in parc ferme, the car can’t be touched. Parc ferme began at midnight, and we finished grooving tires at 11:59 pm. The parc ferme rule never made sense before then; without this rule, we probably would have worked through the night.

Stage One

The transit stages for the Ramada Express Rally are huge. All the stage roads are on the Hualapai Nation on the edge of the Grand Canyon, about 100 miles from Laughlin. In previous years, drivers had complained about the fatigue, monotony and tire wear from the long transits, so the rules were changed this year to allow the cars to do the long transits on their trailers.

To make the race look more exciting for the locals, however, all the cars still drove over the start ramps and through town before loading onto the trailers across the border in Arizona. The American Rally Sport Group has a good record of trying to keep the competitors happy and the rally as spectator-friendly as possible.

Expecting mud, snow and slush on narrow forest roads, we pulled up to the start of stage one and saw a dry, hardpacked straightaway. Just before counting down to our start time, the starter warned us that two cars have rolled on this stage. No pressure… Go!

At approximately 7,000 feet, the Beater accelerated reluctantly to a top speed of about 80 mph. On the dirt, with thoughts of cars on their roofs, it still seemed really fast. After a few minutes of driving flat out, the road suddenly narrowed, got wet and snowy, and turned into a hard right. Less than 10 turns into the twisties, we saw warning triangles, an OK sign, and the Audi quattro of George Plsek and Alex Gelsomino tires up in the ditch. It took serious self control to keep the car on the road as we worked slowly up to speed. An upside-down car on the first stage doesn’t inspire confidence. A few turns later, the scene is repeated, this time with Mark Nelson and John Bellfleur’s Mitsubishi Lancer. This was getting ugly.

When we reached the end of the stage, the arrival time control was at the top of a very small hill, and another car was still busy checking in. We waited halfway down the hill, and then tried to pull forward when the other car moved. We tried.

Even on the very slight incline, we just sat and spun our tires in the mud. Just making it to the time control meant backing up and taking a running start. This was an omen.

Stage Two

Everything was brown. The road was brown, the cars were brown, the trees were brown, the windshield was brown. The road was heavily rutted, but the ruts were nearly impossible to see. They constantly tugged the car this way or that, and steering inputs seemed to have little effect in this slime.

The transit to stage two had two-way traffic, with the leaders, having already finished the second stage, coming head-on toward us on their way to the first service stop. Common sense said to slow down, physics said if we did so we’d get stuck, so there we were, flying through the muck, tires spinning, car sliding erratically from one side of the road to the other. Rhys Millen was doing the same, and we narrowly miss slamming head on into him. As our windows passed within inches, we could see the grin on his face was almost as big as ours. Insanity loves company.

The start of stage two was frozen and slick. So slick, in fact, that as Richard Byford and Fran Olson tried to inch forward to the start, their BMW 2002 did a slow, graceful pirouette and ended up stuck sideways in the road in front of us. Several navigators jumped from competing rally cars to push them from the muck.

The weighty slime so thoroughly coated the sides of our car that the stage workers had to ask our car number before recording our times. Our hearty mudflaps, which had survived all our “testing and development” miles without complaint, were ripped from the car after just two stages in the slime.

Stages three through six were more of the same–slimefests of epic proportions. The mud became so thick at one point that full throttle in The Beater produced all of 35 mph. At the end of day one, The Beater managed an impressive 10th overall, slotting in right after the open class Galant VR-4 of Keith Roper and Ray Damitio and sneaking in just in front of the Group 2 Eclipse of Christopher Burns and Steve Westwood. The next day was sure to be harder for The Beater as the roads opened up and horsepower became more of a factor.

Faster it was, though momentum was proving itself a fair substitute for horsepower for a while. Pounding up stage 7 out of the grand canyon, we managed to hold our position despite the need for power. After a brief roadside repair stop to fix some loose exhaust bolts, we started into the real horsepower stages where the fast cars were going 140 mph, and we were going 100. That lead directly to the ditch (see “Great Moments in Rallying #3, to the right.)

Driving fast on treacherous, slippery roads you have never seen requires a certain placidity, a certain Zen calmness in the face of unparalleled pressure. Every road has a rhythm, every car has its special moves, and being in the zone means being able to make the car dance. Try dancing after crashing a car, running a quarter mile with a helmet on your head and the thin air of 6,000 feet in your lungs, after spending five minutes jumping around in a ditch like a couple of drunk monkeys. This is the kind of challenge that separates the professionals from the dirt jockeys like us.

The very next stage, still breathing heavy, and still searching for our rhythm, it happened again. This time there was no glorious almost-save. This time it was simple. We went too fast, turned too late, and slid into a small ditch. A very hard small ditch. This, for certain, was the end of the rally for Eyesore Racing.

This brings us up to The Hammer, but you’ve already heard that one. Finishing the Laughlin rally’s 45-mile Canyon Challenge stage after repairing the The Beater with The Hammer may turn out to be the crowning achievement in our motorsport careers. The Canyon Challenge came at the end of the day as the sun was setting. And, as luck would have it, the stage ran primarily east to west. That meant the pucker factor was high as The Beater blasted over blind crests, directly into the blinding sun. However, this time, it stayed on the road and made it to the end of the second day.

Leg Three of the Laughlin event is held in a huge gravel field behind the headquarter’s hotel. It’s called the SuperStage and is basically a dirt autocross which pits competitors against one another in wheel-to-wheel brawls designed to put a spectator-friendly finishing touch on the event. Organizers match cars which have produced similar stage times on the rally’s previous legs to compete together on the two-lane SuperStage course.

The Beater was matched against the RX-7 of Jim Gillaspy and Mick Kilpatrick who had eeked out a fair lead on us the previous two days. The SuperStage, however, proved how well matched the cars really were as the two were given the exact same finishing time on two of the four stages. Naturally, Gillaspy’s car was slightly ahead on those runs, but a half car length is invisible in rally time. The other two runs were a draw–one win each. Stage 15 brought to an end one of the longest, roughest and highest attrition races in American rallying in the last 10 years.

In the end, The Beater did all right. Somehow, despite all our efforts to throw it away on stages 10 and 11, The Beater won its class (Group 2) and managed ninth overall–not bad given the number of four-wheel-drive open class cars in this race. And the reward for winning Group 2? One thousand glorious greenbacks! Who says rallying doesn’t pay? The ARSG gave away $25,000 in cash and prizes at the awards ceremony after the race.

The organizers of the Laughlin rally have a slogan: “We promise you an adventure,” they say. And given the roads, distance and fun factor of this year’s event, we couldn’t agree more. The Laughlin International Rally epitomizes what rallying should be: Man vs. road vs. the clock. It is, without question, an adventure.

Read more: http://www.modified.com/projectcars/0107scc_ramada_express_rally_2000/index.html#ixzz1hEqXbxeX

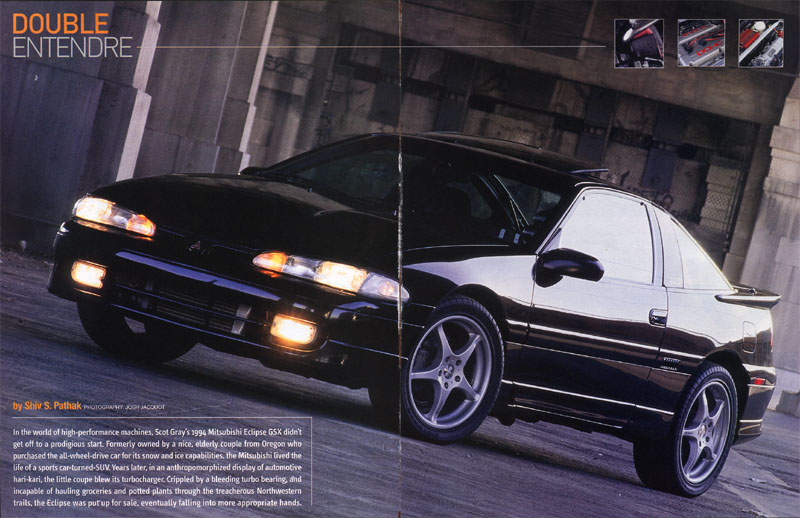

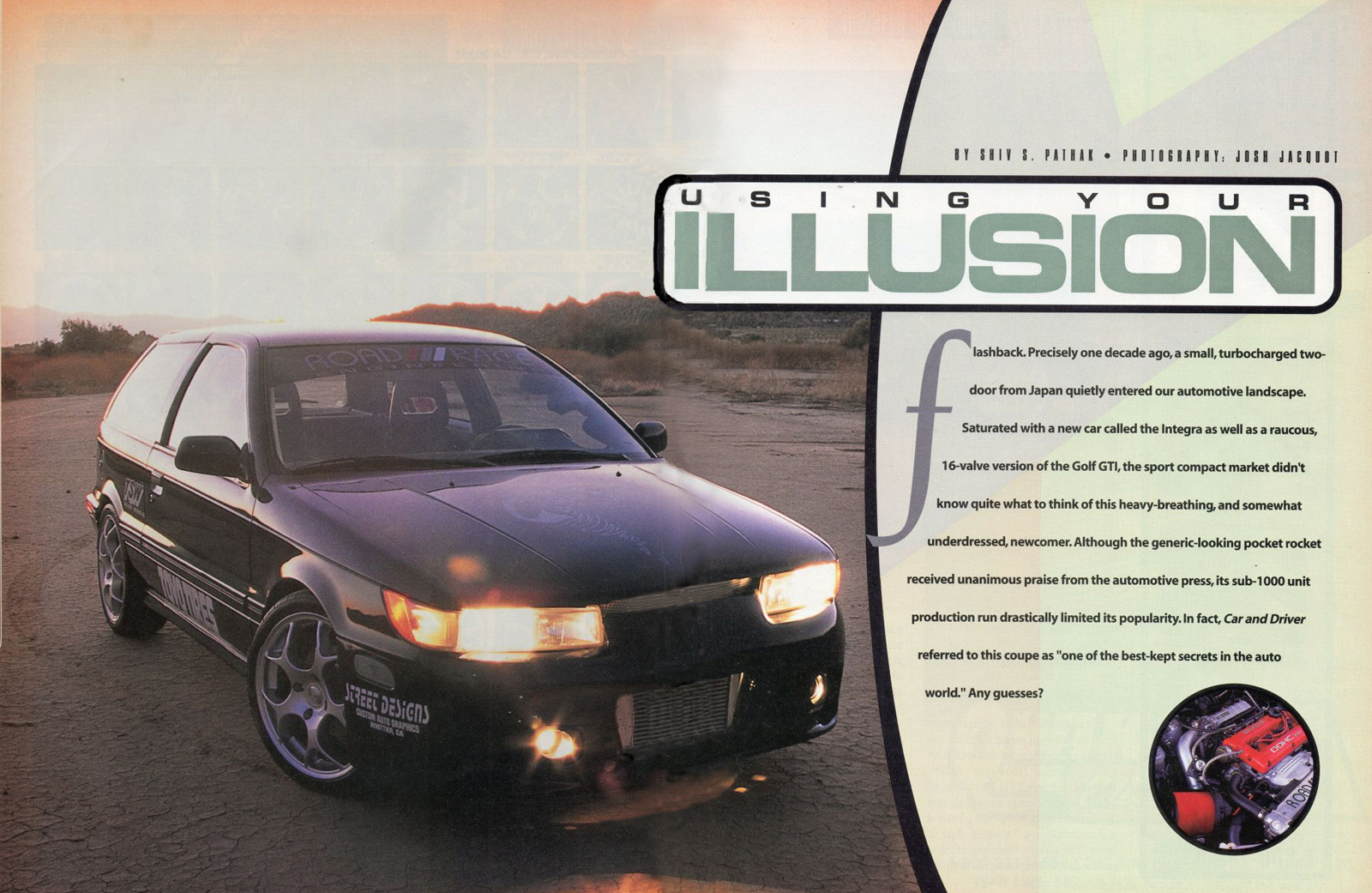

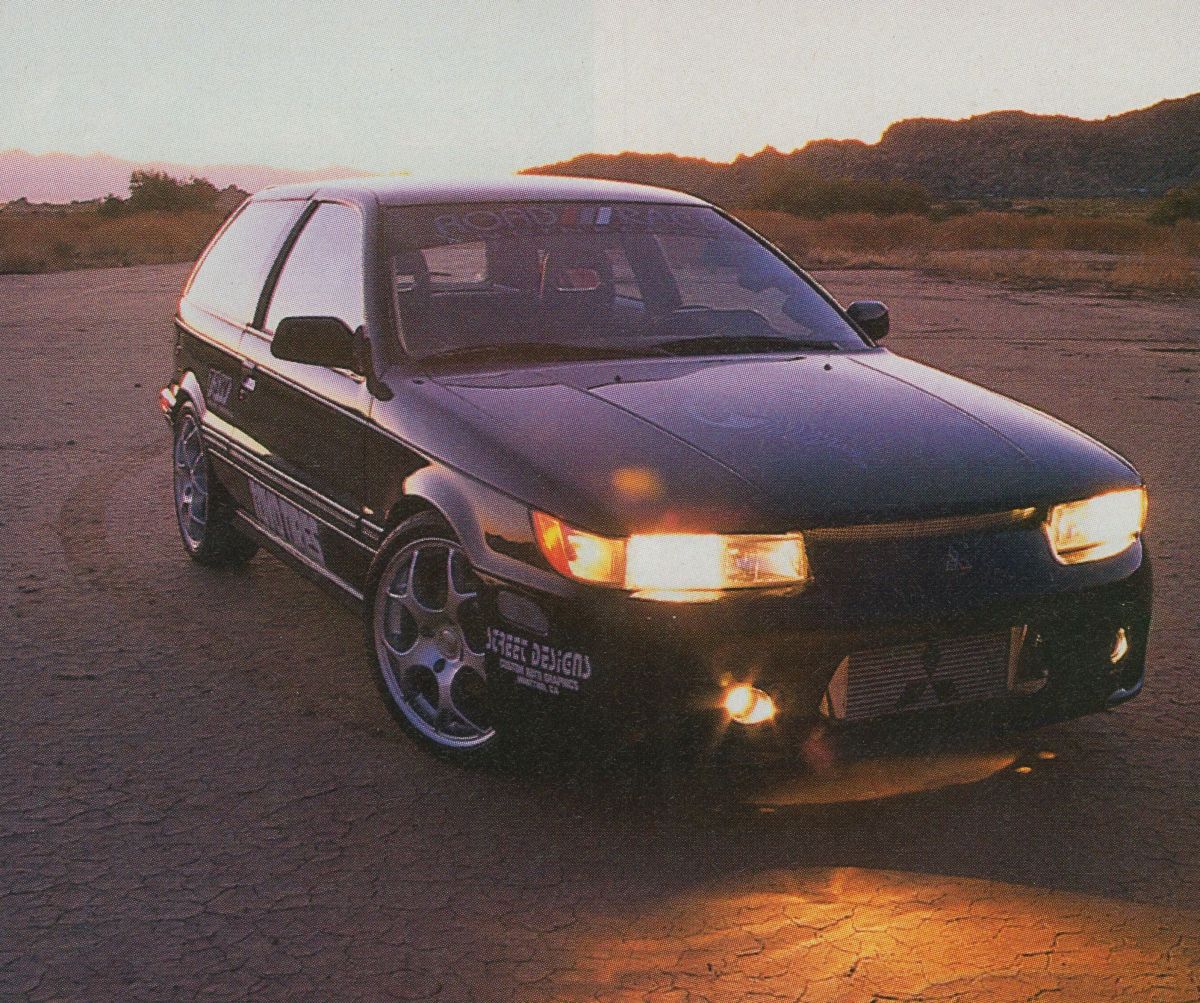

Scot Gray’s Eclipse in SCC Magazine – September 2000

RRE tuner Scot Gray got a nice feature in Sport Compact Car Magazine article on his 1G AWD Eclipse this month.

Double Entendre

By Shiv Pathek

Sport Compact Car Magazine September 2000

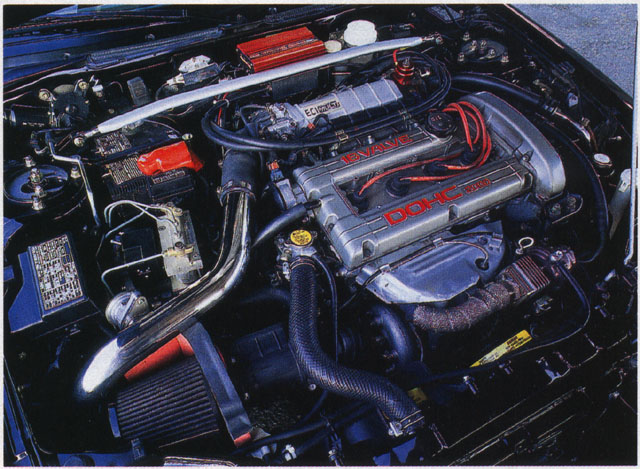

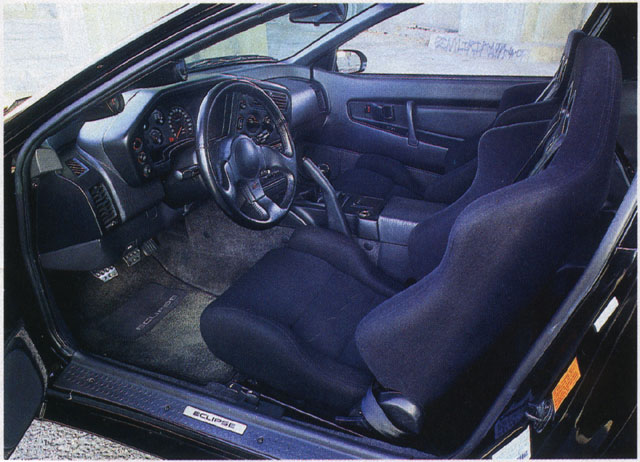

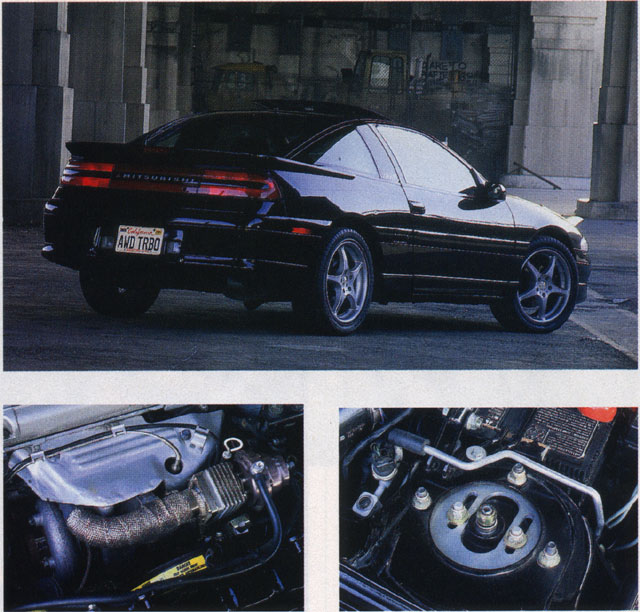

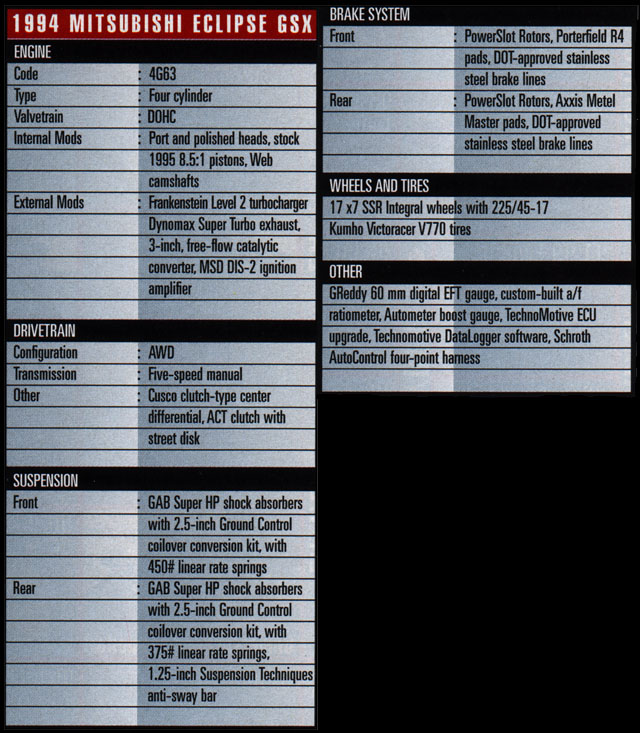

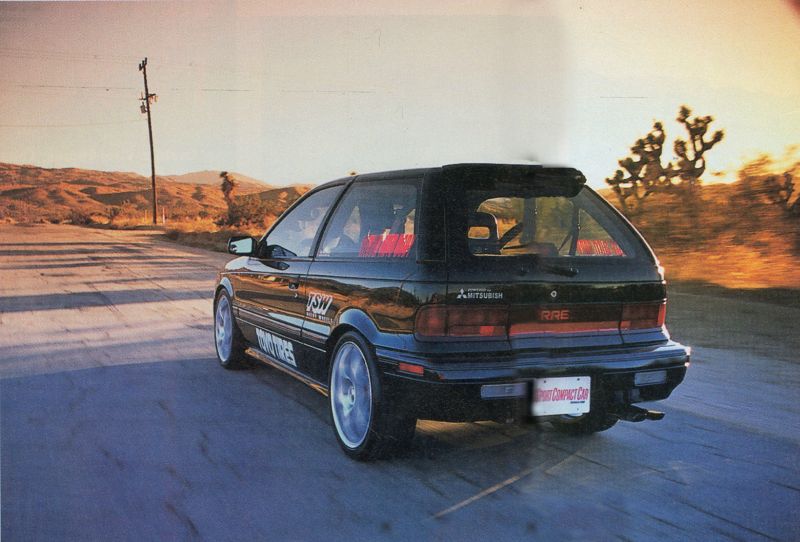

In the world of high-performance machines, Scot Gray’s 1994 Mitsubishi Eclipse GSX didn’t get off to a prodigious start. Formerly owned by a nice, elderly couple from Oregon who purchased the all-wheel-drive car for its snow and ice capabilities, the Mitsubishi lived the life of a sports car-turned-SUV. Years later, in an anthropomorphized display of automotive hari-kari, the little coupe blew its turbocharger. Crippled by a bleeding turbo bearing, and incapable of hauling groceries and potted plants through the treacherous Northwestern trails, the Eclipse was put up for sale, eventually falling into more appropriate hands.

Three years later an abridged performance history of Gray’s Eclipse would have you believing that it has made up for lost time. “I upgraded the turbo twice,” Gray confessed. “The factory turbo performed very well, enabling me to run 13.3 E.Ts in the quarter-mile. Later, I upgraded to a ported and clipped (10 degrees) Mitsubishi 16G turbocharger. This upgrade significantly improved top-end power with only a minimal increase in lag.”

Capable of running mid 12s at the drag strip, all was well until our protagonist ventured to Buttonwillow Raceway, overheated the car and warped the cylinder head. Now bitten by the road racing bug, Gray wasted no time in procuring a new factory head. With the assistance of Road Race Engineering (Santa Fe Springs, Calif.), the unblemished head was thoroughly ported and polished. The bottom end, receiving its fair share of attention, was rebuilt with the inclusion of stock 1995 model year 8.5:1 pistons.

On the road, the performance improvements were obvious. Perhaps a little too obvious, as the combination of higher compression pistons and better-flowing heads resulted in a nasty case of boost creep. To remedy the situation, a generously sized external wastegate from TIAL was ordered. But somewhere between the order and the delivery process, Gray decided to up the ante even further.

“I decided to upgrade the turbo [again] to make full use of the new wastegate.” After a quick long-distance call to Texas Turbo, a “Frankenstein Level 2” turbocharger was on the way. Of course, swapping turbos and wastegates isn’t as easy as it sounds. with different flanges and wastegate configurations, Road Race Engineering had to craft a custom 3-inch down-pipe and exhaust manifold.While all this fabrication sounds like a lot of work, there is no doubting its merits. Empirically, the new turbo should be capable of generating more airflow, with less heat and with reduced exhaust back-pressure levels—all of which translate to more horsepower. However, airflow is useless without sufficient fuel delivery and properly timed spark advance.In an effort to meet both requirements, Gray installed a TechnoMotive ECU upgrade. Featuring a number of welcome EPROM tweaks, this cost-effective upgrade removed the boost and fuel cut in addition to raising the rev limiter. As an added bonus, the stock low-resolution, dashboard-mounted analog boost gauge can easily be configured to monitor air/fuel mixture, ignition timing, battery voltage or knock sensor output. Coupled with TechnoMotive’s optional data logging system, Gray is able to tune the car for maximum power with minimal drivability compromises. In fact, despite driving a car capable of whipping off mid-11-second passes, Gray claims to record better-than-stock fuel economy (25/20 hwy/city to be exact).

“I decided to upgrade the turbo [again] to make full use of the new wastegate.” After a quick long-distance call to Texas Turbo, a “Frankenstein Level 2” turbocharger was on the way. Of course, swapping turbos and wastegates isn’t as easy as it sounds. with different flanges and wastegate configurations, Road Race Engineering had to craft a custom 3-inch down-pipe and exhaust manifold.While all this fabrication sounds like a lot of work, there is no doubting its merits. Empirically, the new turbo should be capable of generating more airflow, with less heat and with reduced exhaust back-pressure levels—all of which translate to more horsepower. However, airflow is useless without sufficient fuel delivery and properly timed spark advance.In an effort to meet both requirements, Gray installed a TechnoMotive ECU upgrade. Featuring a number of welcome EPROM tweaks, this cost-effective upgrade removed the boost and fuel cut in addition to raising the rev limiter. As an added bonus, the stock low-resolution, dashboard-mounted analog boost gauge can easily be configured to monitor air/fuel mixture, ignition timing, battery voltage or knock sensor output. Coupled with TechnoMotive’s optional data logging system, Gray is able to tune the car for maximum power with minimal drivability compromises. In fact, despite driving a car capable of whipping off mid-11-second passes, Gray claims to record better-than-stock fuel economy (25/20 hwy/city to be exact).

Like the engine, the rest of the car has been set up with both street and track use in mind. For a clutch, Gray chose a sturdy Advanced Clutch Technology 2,600 ft./lbs. pressure plate with a streetable organic friction disk. To strengthen the Eclipse’s notoriously fragile drivetrain, a Cusco clutch-pack center limited slip differential was installed. Supporting all four corners are GAB Super HP shock absorbers with 2.5-inch race springs and adjustable threaded spring perches from Ground Control. To ameliorate some of the Eclipse’s nose-heavy handling balance, Gray installed a 1.25-inch rear anti-roll bar from Suspension Techniques. And of course, a good road racing suspension wouldn’t be complete without a sticky set of R compound tires.

So how does it drive? Ridiculously well, that’s how. With a 0-to-60 mph sprint taking a mere (and official) 3.8 seconds, Gray’s Eclipse is one of the quickest cars SCC has ever tested. Quite remarkable ending for a formerly pedestrian go-getter.

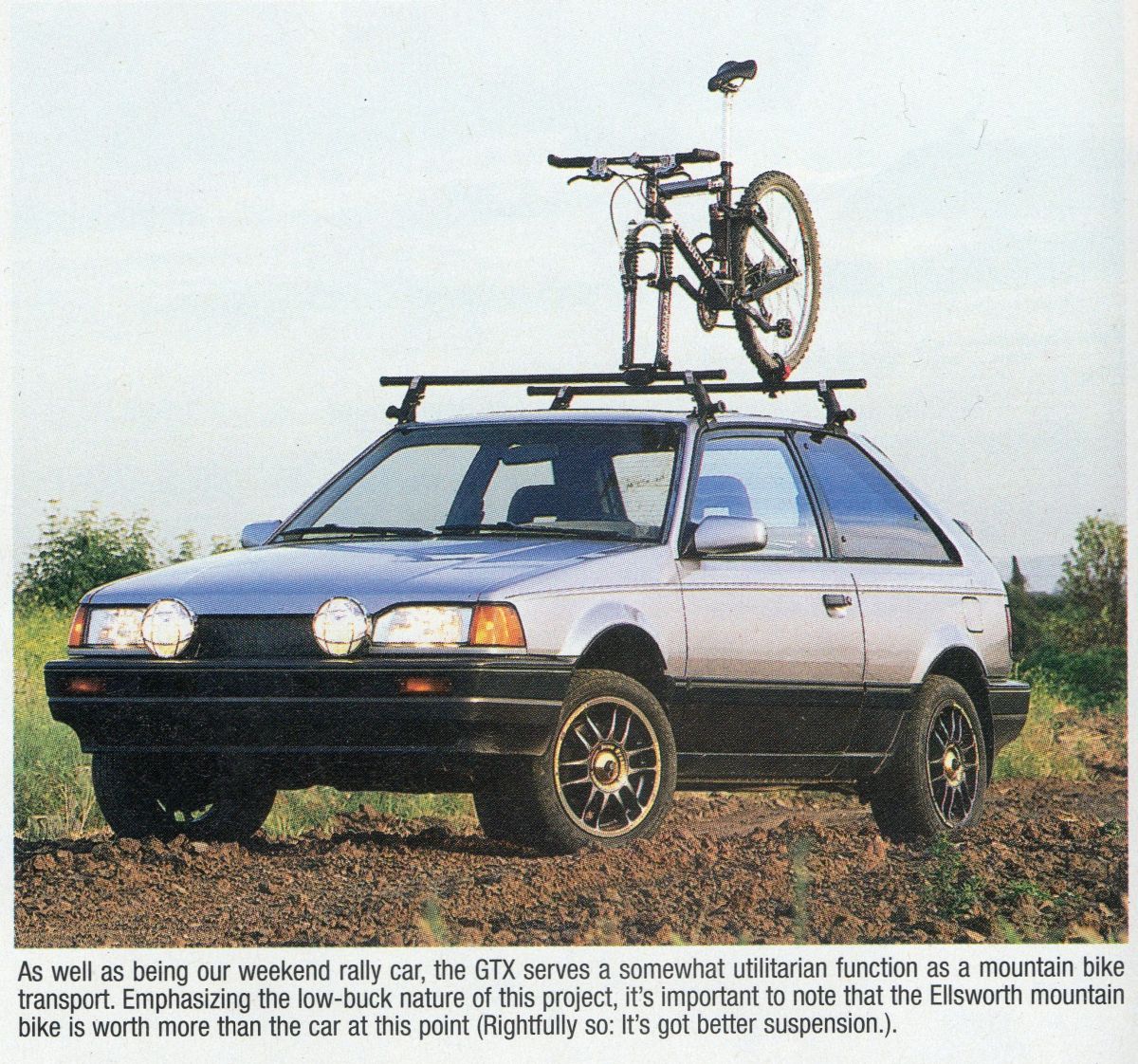

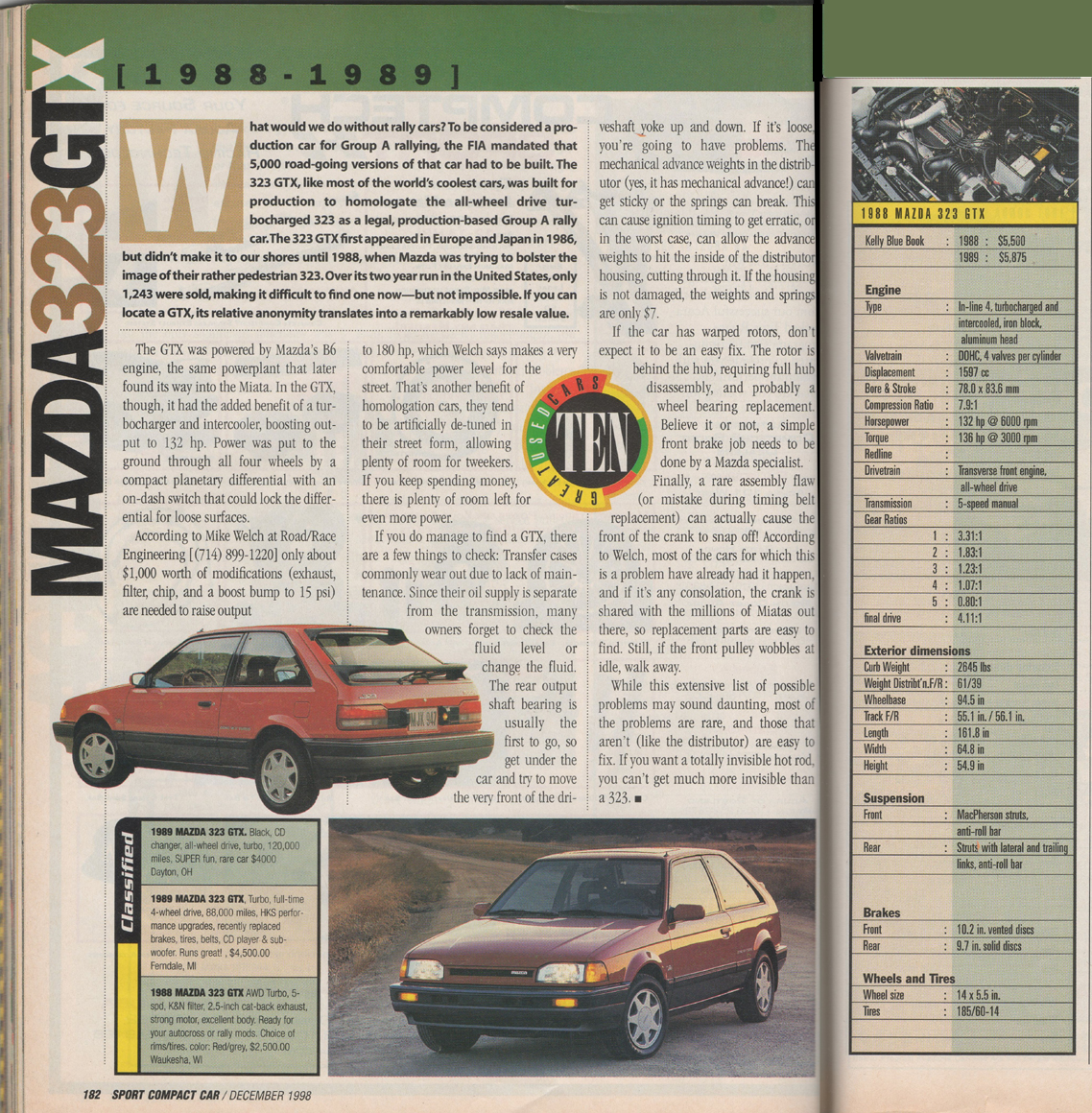

Sport Compact Car Magazine – Project Mazda 323 GTX: Part 2

Here is Josh Jacquot’s and Dave Coleman’s 2nd part of Project 323GTX. We no longer sell parts for this car since they have to be custom made on the car in the shop. But since I got my start working on AWD rally cars on the 323 GTX working for Rod Millen back in1990 I always have aspecial sentiment for these little cars.

In this article we helped the SCC Mag guys with the GTX’s suspension, brakes and rebuilding the distributor.

Sport Compact Car Magazine

September 2000

Written By Josh Jacquot

Photography by Les Bidrawn, Dave Coleman, Josh Jacquot

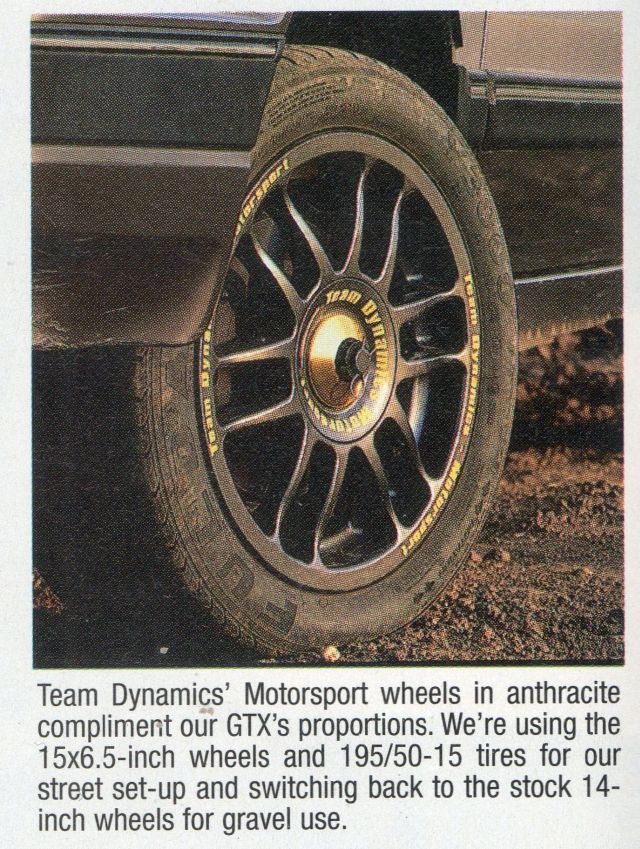

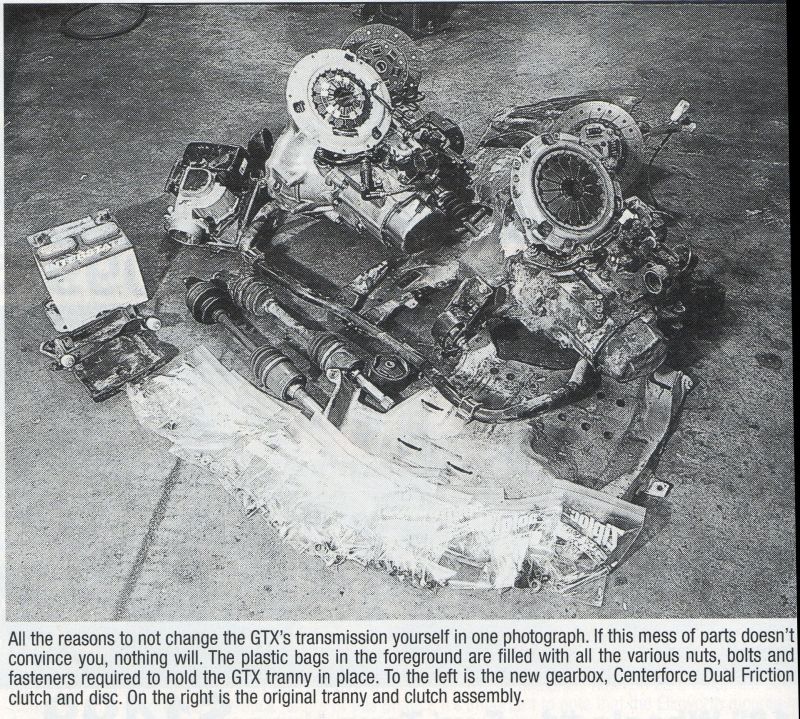

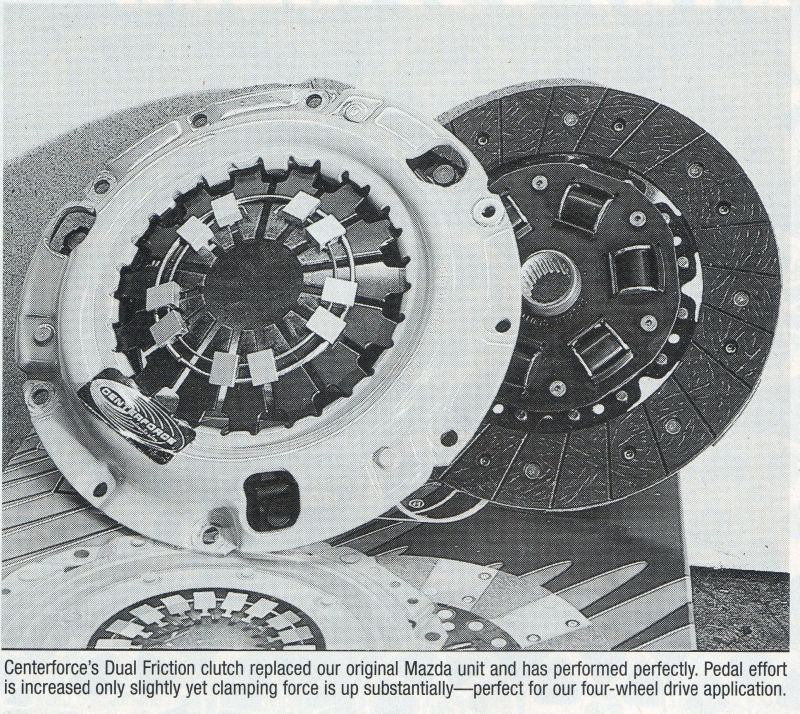

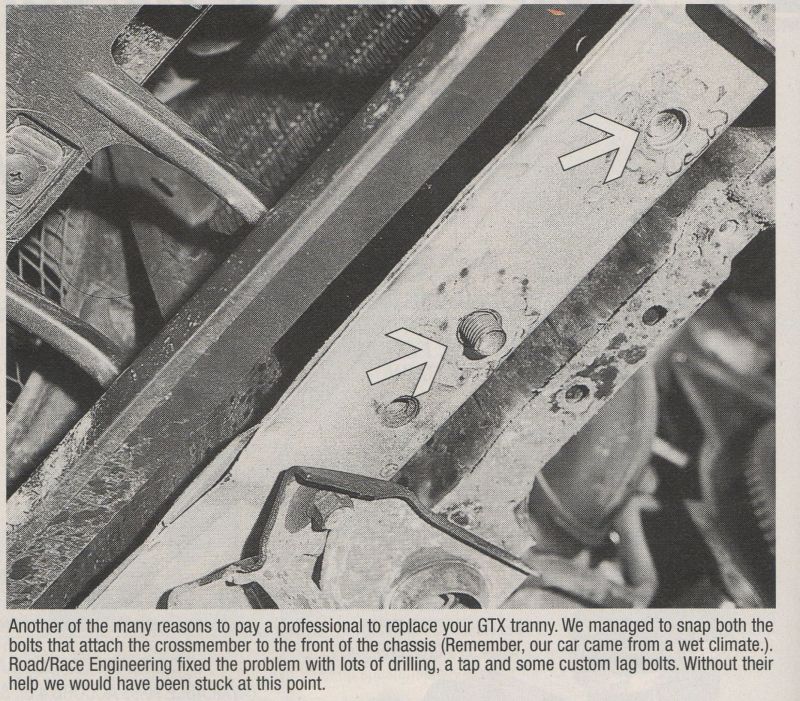

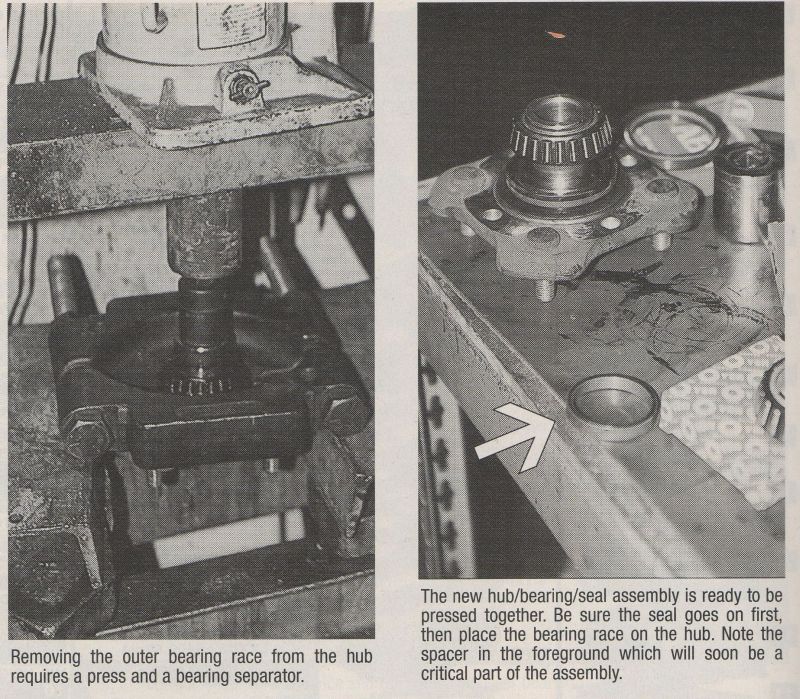

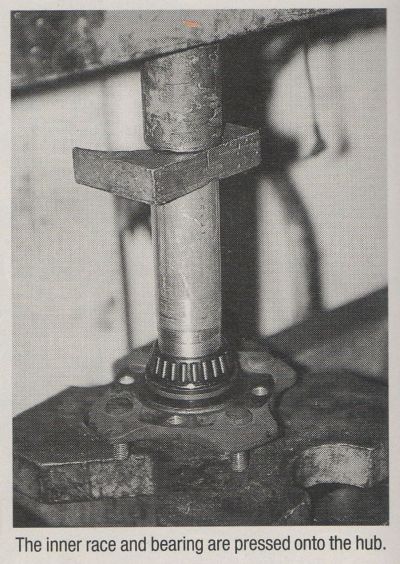

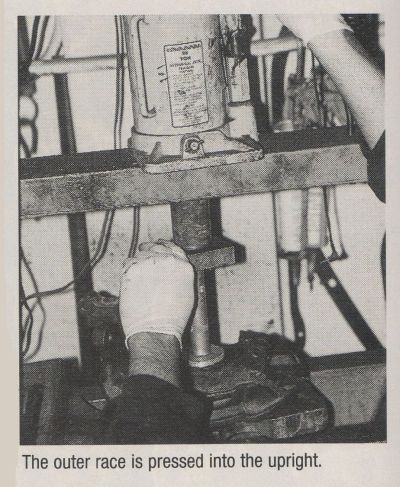

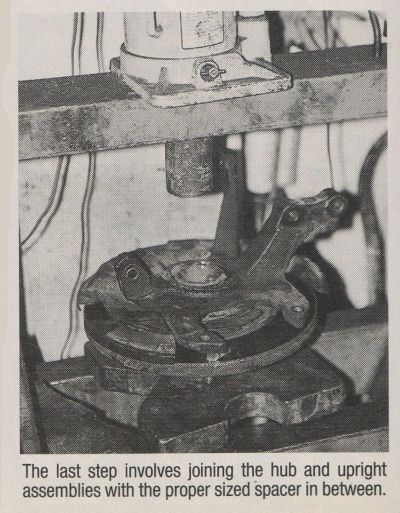

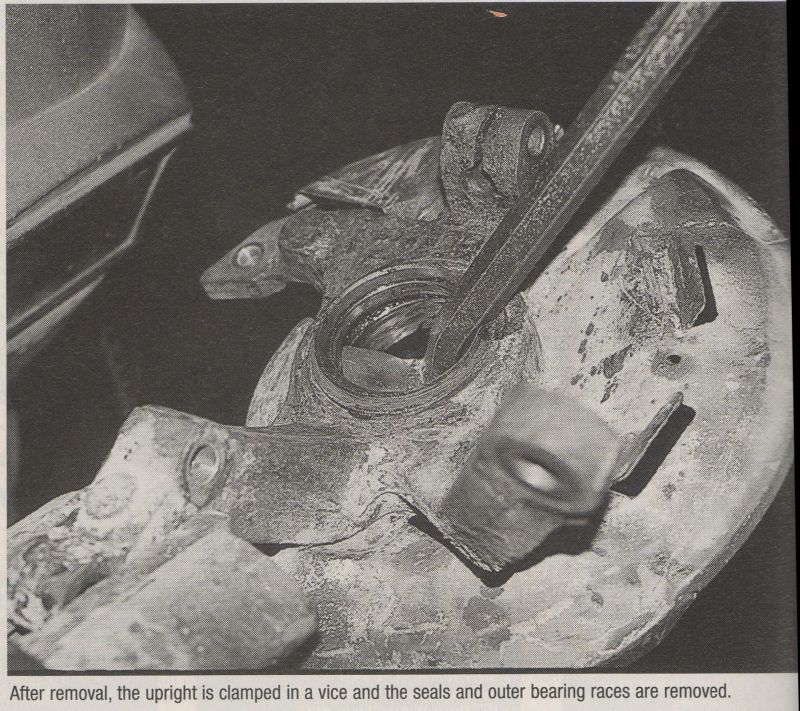

The resurrection of our Mazda 323 GTX project car is still in its infancy as we continue with the essential repairs we began in the first installment. In case you missed out last month, we covered the replacement of the transmission and clutch as well as the basics of a wheel bearing rebuild. This month, we’ll tackle the GTX’s suspension, distributor and brakes, as well as a few less critical aesthetic add-ons.

The GTX’s reliability (considering the regular pounding it receives) as well as its overall capability in the dirt continues to amaze and impress us all. It’s proving itself daily as one of the most fun and most practical cars around the office. While it may not impress anyone with its looks, every time we get behind the wheel, we remember why we had to have a car to play in the dirt.

Springs and Shocks

With what seems like several feet of rubbery suspension travel, the 323 isn’t very much fun when wearing worn-out shocks. This is a real problem and is something the GTX community is tackling in hundreds of creative ways. We aren’t going to pretend that there’s a simple solution either. No one has made new GTX-specific dampers in this country for years. Tokico Dirta struts went out of production several years back and very few, if any, shocks offer the kind of damping control required by the GTX’s long-travel strut system. Cork Sport, an Oregon-based Mazda specialty company still imports KYB struts for the car. However, they aren’t exactly what we were looking for, so the search continued.

Our solution? Buy used. We can’t, obviously, give our wholesale endorsement of this sort of upgrade, but in our case, it has worked fine so far. Given the lack of new suspension parts for these cars, this may be your best option if you decide to follow our lead. The 323 GTX listserv (www.egroups.com/group/323gtx) is likely the best place to look for used GTX parts and information.

Since our infatuation with 323 rally cars began a few years back, we’ve made friends with several 323 owners who race their cars in the California Rally Series and other SCCA events. This put us in good company when it came time to look for used suspension parts. Paul Timmerman (a local racer whose GTXs we featured in the January ’99 issue of SCC) and Road/Race Engineering came to the rescue.

Timmerman had a set of used GAB struts from an old Production GT 323 racecar he was keeping around as race spares. However, since he was planning to upgrade to a custom Bilstein coil-over setup in the near future, the parts that were currently on his car were about be spares. The timing was perfect and we stepped in with the cash. Timmerman gave us a generous price, which didn’t hurt the cause either. The front struts were fitted with stock-diameter rally springs but the rears had no springs. So, despite all our efforts and waiting, our wanna-be rally suspension still wasn’t complete.

Road/Race to the rescue. Naturally, Welch had the solution to our problem in the form of RRE’s coil-over setup. At $400 for all four corners, this reasonably priced setup allows an inch of adjustability–either up or down–from the stock ride height. We only needed half the kit since we already had front springs.

Welch chose 150 lb/in springs for the rear of the car, which he figured would complement the rather hefty looking front springs. At this point there was still no real way to know the rate of the front springs without disassembly and we were in a hurry to get the suspension together. Luckily, Welch has enough experience with these cars that we knew his estimate would be better than our guess. We plan to complete the coil-over kit in the future anyway, thereby eliminating the guesswork involved the spring rates. However, since this vehicle will be primarily a dirt car, the precision and exacting demands of dialing in a tarmac set-up don’t exist. If it worked well in the dirt, didn’t bottom out and rotated quickly, we would be happy.

Installation for the rear springs was as simple as sliding the sleeves over the strut body, threading on the collars, dropping on the spring and bumpstops, and then bolting the whole assembly together. We used the stock bumpstops but trimmed off the bellows section.There was still more than an inch of bumpstop to save our GABs from dangerously bottoming out, but with the added travel and increased spring rate, we figured that wouldn’t be a problem (and it hasn’t).

The fronts bolted into place with the same ease that everything else on the car had exhibited–rusted bolts, nuts and washers were the name of the game. We managed to get the struts out without breaking anything or rounding off any bolt heads. Fitment of the GAB strut housing required removing small amounts of material from the 323’s upright to achieve reasonable camber settings. This job was easily accomplished with a die grinder and a bit of patience.

Per Welch’s recommendation, we didn’t re-fit the front anti-roll bar after replacing the transmission. Reducing the GTX’s front roll stiffness enhances its ability to rotate quickly in the dirt–something real rally cars do very well. The rear anti-roll bar bushings were destroyed from years of wear and weather so we replaced them with RRE’s polyurethane anti-roll bar pivot bushings and new end links (which use rubber bushings). The original end links and bushings for the rear anti-roll bar had become one with the car after years of weather and wear and required some work with the sawzall and several choice words to remove. The new hardware went into place without any problems and took the slop out of the system.

We were initially quite concerned with the alignment settings of Project 323 GTX and asked our friends at Wheel Warehouse in Anaheim, Calif. to handle the job. However, after they could barely squeeze zero camber (Welch’s recommended dirt setting) out of the front end we were less serious about radical alignment. The problems in the front came from our less-than-precise method of grinding the uprights–a not-so-scientific way to get the GAB rally struts to fit. We simply set the car up to go straight down the road and quit worrying about toe and camber, since we are planning to spend most of our time in the dirt, where these settings become insignificant anyway.

Distributor

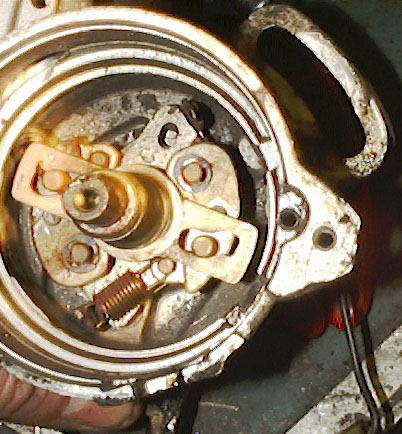

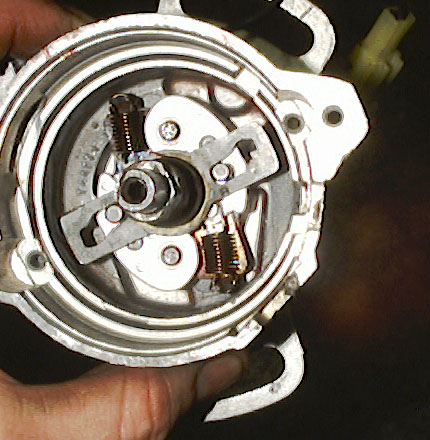

The GTX uses a mechanical-advance distributor to control spark and therefore suffers the consequences of such a complex design. The mechanical advance springs on most high-mileage GTXs fail, allowing the advance weights to swing into the distributor housing as the assembly spins. The weights then rub against the side of the housing, eventually cutting it in half if, not repaired. They also allow the engine to run with maximum mechanical advance of about 30 degrees BTDC. We found all this out the hard way.

Our car had just about every distributor problem the GTX can exhibit. Not only had the advance springs failed, cutting through the distributor housing and allowing maximum advance at all times, but the advance plate, which rotates on ball bearings had seized, allowing for very little, if any, vacuum advance or boost retard. Yet, through some miracle of God-given grace, the car made it 800 miles from Salt Lake City to Southern California in its initial run home.

The distributor is easily removed from the 323 with only two bolts, several electrical connectors, the spark plug wires and one coil wire. (We guess that’s simple, anyway). Be sure to note where the rotor is pointing upon removal and return the distributor to that position when reinstalling. Also, it’s critical to not turn the engine over while the distributor is removed or you’ll end up spending hours trying to time the engine correctly.

Our distributor was removed easily enough, but refused to come apart for a rebuild. We ended up using the most elegant method we could think of for disassembly. Out came the cutting torch and pry bars as Welch pounded, heated and pried until the entire assembly was in pieces. Graceful it wasn’t. But we eventually reached the source of our problems and were able to replace the advance springs and rebuild the advance plate, which controls vacuum advance and boost retard. The new springs (which RRE sells for $7) utilize a plastic reinforcement where they attach to the advance weights–we don’t expect any more problems here. However, due to the broken springs, the weights had worn a hole completely through the distributor housing. Welch patched the hole with epoxy since it wasn’t large enough to cause structural fatigue and began reassembly of the numerous distributor parts. We also replaced the distributor cap, since it was cracked in several places surrounding the contacts.

All the problems listed above are common to GTX distributors, so don’t be surprised if your car exhibits similar failures. We were lucky enough to have all of them. However, despite the many parts and complexity of the GTX’s distributor, it’s possible for most weekend wrenchers to tackle its rebuild. Careful disassembly goes a long way in putting things back together in the right order. Plus, the parts that fail are cheap. If you’re still not up to the task, send your distributor to Road/Race and they’ll handle the job for $100.

Brakes (or Lack Thereof)

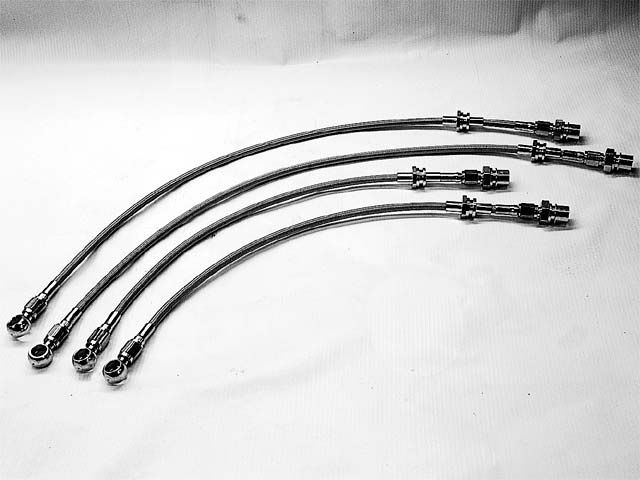

Stopping our GTX has been a bit of challenge since this project got off the ground. A mushy pedal is never very confidence- inspiring, especially in a car that will be driven with any enthusiasm. It didn’t take long underneath our GTX to notice the extreme wear on the original brake lines. The lines were cracked and worn, and had a generally dangerous look about them. We figured an upgrade to RRE steel braided lines couldn’t hurt. At this point it seemed safe to assume replacing the lines and thoroughly bleeding the brakes would bring back a stiff pedal. However, after doing so, we soon realized the problems with our GTX’s brake system go beyond simple line replacement.

Welch tells us that it’s not uncommon for GTX calipers to lose some off their free play over time. Apparently, the calipers’ self-centering mechanism seizes with exposure to moisture and dust after years of use. The resulting twist in the calipers causes excessive pedal travel, regardless of new brake lines. So we’ll be treating Project 323 to a caliper rebuild and some new brake pads in the next few months to bring back some solid pedal feel. In the mean time it still stops well, so we’ll survive.

Always Accessorize

In our effort to make a reliable and inexpensive rally car, we ran across a few other necessities that we just had to have. What was the one thing that all rally cars had that we were lacking? The answer was simple: Huge, night-killing driving lights.

Toucan Industries stepped up with a set of Super Road Boy 100-watt driving lamps. The lights come with a complete wiring diagram, wires and an on/off switch. Our mounting requirements forced us to mount the giant lights upside down–not the most aesthetically pleasing solution, but this car is all about function, not form. Plus, our mount requires no drilling into the bumper. We used 1 x 1.5-inch box section aluminum as a mounting bracket for the lights. The back of this box section bolted to the original grille mounting bracket at either end of the main grille opening. The front of the bracket bolted directly through the lights’ rear housing–a simple mounting solution, which only took a few hours to assemble. We obviously removed the GTX’s unique grille and replaced it with a section of grillwork we found at the hardware store. The new grill isn’t exactly beautiful (in fact, it’s pretty ugly) but, judging on looks alone, it flows considerably more engine-saving cooling air than the original.

Next Time

Hopefully we’ve covered the majority of the major repairs necessary to keep the GTX in running order as a daily driver. We’re counting on it regularly for transportation and recreation these days, so it’s necessary that it not leave us stranded. Next time we’ll begin with the basic power upgrades as recommended by Road/Race Engineering and hopefully have a few dyno charts from local competition GTXs for comparison. Until then, rally on…

Sizing it up

Assuming you’ve already run across the SCC Rallycross Smackdown story last month, you know how effective a properly prepared GTX can be in the dirt. However, we always want a back-to-back, before-and-after comparison to quantify the effectiveness of the changes to our project cars. Before doing any of the above-mentioned work to the car, we staked off a section of dirt road in the nearby forest and went to work. The road, an unbelievably twisty section of gravel with huge elevation changes, ranks among the best gravel roads any of us have ever seen.

Project GTX bobbed and weaved with engineering editor Coleman clinging for dear life in the passenger seat during our initial runs. Don’t bother repeating this test on your own, as its stupidity exceeds even our grossly skewed limits of sanity. We made the runs again after all the repairs and with the much-improved rally suspension in place.

So, what did all this insanity prove? Mostly that the changing conditions of dirt roads aren’t so good for comparing improvements in rally car performance. Without question, the new suspension, improvements in ignition advance and overall preparedness of the car made it easier to drive and faster in any conditions. However, because of our wet spring and consequent road grating, our test road was in considerably different shape during our second visit. With a much softer surface and more loose conditions our times don’t show the improvement we had hoped for. What they do show, if one looks closely at the raw times (not listed here), is that the GTX is now much more predictable and easier to handle over rough terrain. In fact, the GTX’s ability to devour washouts, ruts, rocks and any other dirt road impediment is simply amazing. Before the upgrades we were operating on faith, now we drive with confidence. See the map and elevation profile on the next page for more details.

Full Article on Modified Magazine:

http://www.modified.com/projectcars/0009scc_mazda_323_gtx_part_3/index.html#ixzz1h9r51Zsi

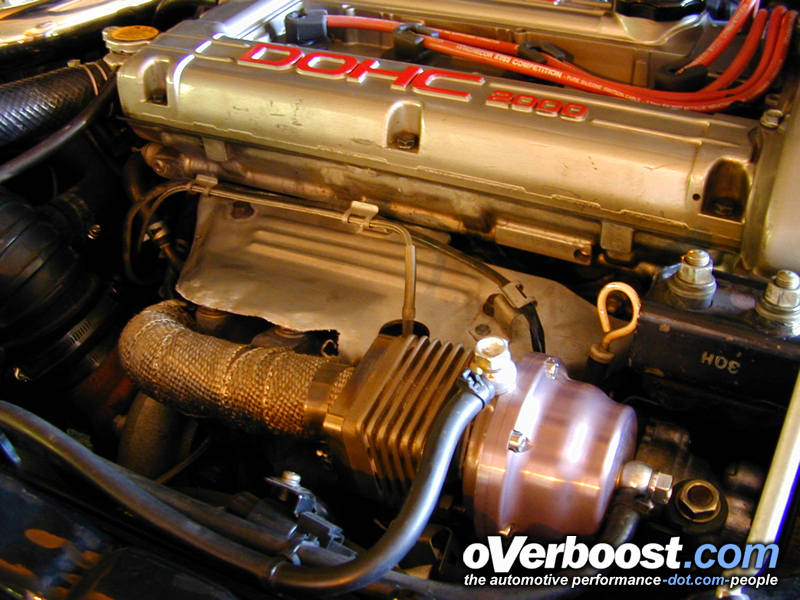

Scot Gray’s Eclipse GSX Featured on Overboost.com

Scot’s GSX just got shot for SCC magazine and will be coming out next month there. Here it is on www.overboost.com right now:

1994 Mitsubishi Eclipse GSX

8/25/2000

John C. Naderi

Throughout the DSM circles and chat forums the tales surrounding this car (and its owner’s prodigious driving talents) have grown to mythical proportions. We know this because our web architect is the proud owner of our Project Eclipse and he constantly regales us with starry-eyed stories about this car’s exploits. We’ve heard many different accounts of this car and driver manhandling Porsches, Ferraris, Vipers and ‘Vettes on strip and street circuits. With this in mind, we nervously ventured out for an appointment with the man who belongs to this legendary machine. Upon our arrival we half-expected to find a Thor-like gladiator standing next to the Batmobile in front of some fog-enshrouded castle.

What we found was actually a mild-mannered Scot Gray standing in front of his equally mild-mannered 1994 Mitsubishi Eclipse GSX. After we completed our photo session Scot agreed to take us for a “relaxing” drive through the hills by his home. Once behind the wheel Scot quickly shed his Bruce Wayne image. Straight line acceleration runs are not really dramatic affairs as the all-wheel drive delivers you to warp speed in the same fluid fashion as the Millennium Falcon. But it was through the twisties that both the Eclipse and Scot’s tremendous driving talent shone through. We’ve had the opportunity to be both pilot and passenger in some of the most powerful race and street machines on every circuit from Willow Springs to the Nürburgring but nothing could have prepared us for this ride. “I’ve been to Skip Barber’s school and I’ve put the car through over 120 track sessions,” Scot told us nonchalantly. This was not cocky bragging on his part but rather something he probably says to alleviate passengers before reducing them to frightened, whimpering sacks of limp flesh.

Our brief ride with Scot confirmed the many fantastic tales we’ve heard so many times before. We’re obliged to report that both the car and driver, do indeed live up to the hype. Through a series of second and third gear hairpins and sweepers we experienced firsthand the Eclipse’s incredible adhesion and slot car-like transitions. “You have to drive it brave,” Scot says in terms of the GSX’s quirky AWD demeanor. In order to demonstrate Scot trails the throttle into a hard left and we begin to plow directly into the side of a rather solid looking mountain face – it takes a heavy right foot to bring things back under control. During a recent paper magazine test (one which the little black DSM dominated in virtually every category) even the highly-skilled automotive journalists couldn’t get a handle on the Eclipse – as indicated by the heavily “chunked” front tires (those who can’t drive cars, write about them-OVB).

But it was on Malibu’s famed Kanan Road that we felt the true power of the beast. We happened upon a Fly Yellow Ferrari 360 Modena and a black 911 Turbo (993). As we slowly came around the pair of supercars Scot blipped the throttle a couple of times but the Ferrari owner wouldn’t bite (probably one of those Hollywood types more concerned with how he looks in the car as opposed to how he drives it-OVB). But for a brief moment the Turbo driver gave chase – we say “brief” because in that moment Scot reduced the Porsche to a tiny spec in the rear view mirror – a mirror that reads – “Objects in mirror are getting their asses kicked (perhaps Scot’s only concession to ego, albeit well-deserved-OVB).” Even if the Stuttgart Wunderkind had run full-out it would have still been futile. Look at these numbers:

|

Car Comparisons

|

||||||

|

0-60 mph

|

0-100 mph

|

1/4-mile

|

top speed,

mph |

lateral g’s

|

hp

|

|

| Ferrari 360 Modena |

4.6

|

11.1

|

13.1 @ 110 mph

|

175 (gear limited)

|

0.92

|

395

|

| Porsche 911 Turbo (996) |

3.9

|

8.9

|

12.3 @ 116 mph

|

192 (gear limited)

|

0.93

|

415

|

| Scot Gray’s Eclipse |

3.6

|

8.9

|

11.92 @116.4 mph

|

178 (gear limited)

|

1.06

|

490

|

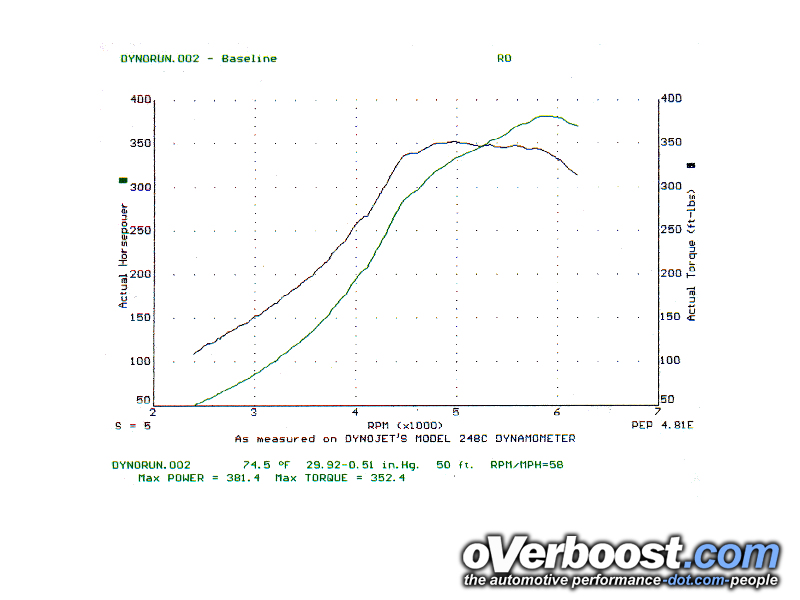

But when the weather outside turns frightful the Porsche and the Ferrari may turn tails (literally) but with a flick of the wipers the AWD Eclipse is ready to go. Zero-to-sixty in the wet still comes up in 3.9 clicks and on a puddle-laden skidpad the little black coupe will still hold 1.02 g’s. The 490 horses under the hood equates to 412 when measured on the Dynojet 248C. While this is the most recent dyno sheet but Scot tells us that the car makes noticeably more power now. So how did Scot Gray manage to turn his Eclipse into the supercar stalker you see here?

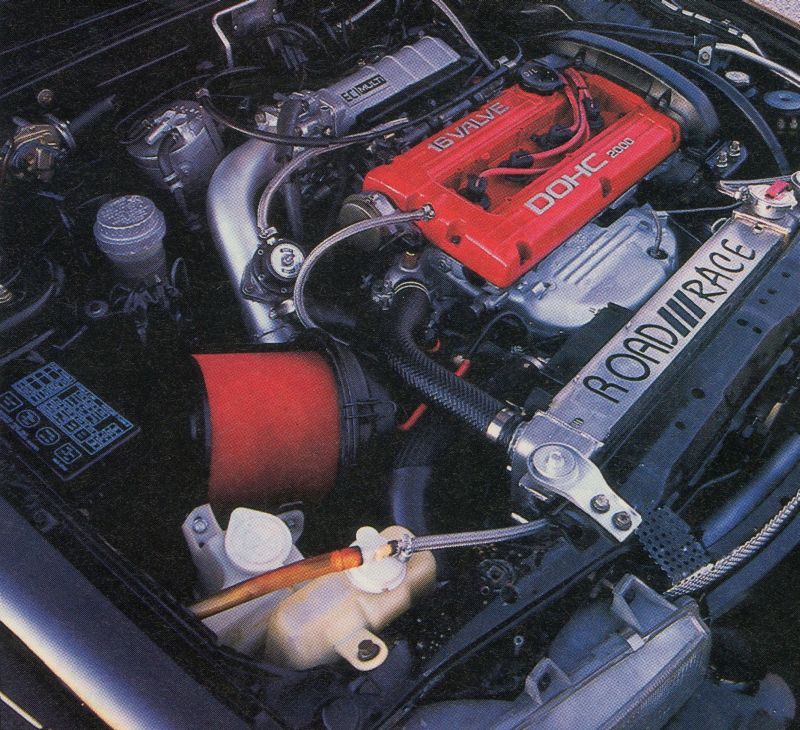

As the song lyrics go, Scot gets by with a little help from his friends. The Eclipse’s monumental performance upgrades are courtesy of Road/Race Engineering. It is safe to say that the crew at this Huntington Beach, California shop knows a little something about Diamond Star cars. The Road/Race crew is revered as god-like when it comes to DSM tuning. These guys know all the tricks and they utilized them on Scot’s Eclipse. The factory head was ported and polished and treated to an HKS Metal Head Gasket and ARP Head Studs. A ’95-Spec exhaust manifold was ported as was the throttle body elbow and MAF Sensor. The stock bump sticks were tossed in favor of a pair of Web Cam units. But the real gem under the hood is the Frankenstein Stage 2 Turbo from Texas Turbo. The high-output turbine is complemented by a “crushed” stock blow-off valve, TIAL External Wastegate, HKS front mount intercooler, an Intercooler sprayer (custom-fabricated with help from Home Depot), RRE intercooler piping, Buschur Racing polished upper intercooler piping and a 3-inch RRE O2 Eliminator Downpipe.

Big turbos produce big heat and since the massive HKS front mount occupies such a large frontal area RRE supplied one of its “Racing” drop in radiator replacements and Scot fabricated a clever ducting system to direct fresh air to the engine bay. In addition to extra cooling big turbo set-ups require extra fuel and this was accomplished with a CarTech External Adjustable Fuel Pressure Regulator, Blitz 660cc injectors and a hardwired Walbro 255Lph HP in-tank fuel pump. Waste gases exit through a Random Technology 3-inch high-flow catalytic converter to a 3-inch RRE exhaust with Dynomax SuperTurbo muffler.

Engine management is assisted by a TechnoMotive Stage III ECU and Data Logger, A’PEXi AFC and an MSD DIS-2 Ignition Amplifier and 2 Stage Rev Limiter. Scot monitors the engine vitals with a GReddy Turbo Timer and Digital EGT gauge and an AutoMeter boost gauge. And, believe it or not, Scot uses a Radio Shack intake temperature gauge, narrow range LED A/F meter and an A/F ratio digital-volt meter.

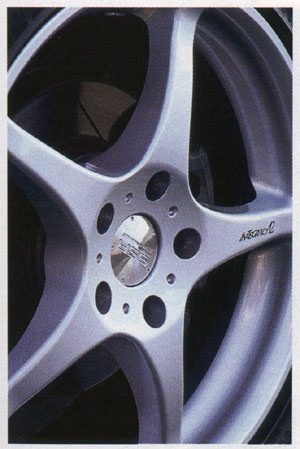

Scot enlists a wide variety or tire/wheel combinations to help him create supercar stats on the streets, strips and circuits of Southern California. On the street Scot rolls on SSR Integrals in a 17×7 fitment with Bridgestone Potenza rubber. For the drag strip he uses his stock 16-inch alloys with Dunlop SP8000s inflated to 20 psi. Scot tells us this provides a relatively low traction combination so the car will spin all four tires briefly off the line and help spool the turbo (good-OVB) and not snap the axles (bad-OVB). Four hundred and ninety horsepower and AWD make for intense drivetrain abuse. The Eclipse’s five-speed tranny is beefed up with a Quaife Torsen-style center differential and an ACT 2600 Street Disc clutch with a lightened flywheel (Scot says even this clutch is prone to slippage). For circuit racing on a real track Scot’s current choice is 16-inch Prime 5-star wheels with Kumho VictoRacer V700 Rs or Toyo Proxes RA1s – depending on what is available. But Scot claims these wheels are ridiculously heavy and really ugly (his wording not ours – OVB legal department), but hold air and fit on the car. He is planning to replace them with Kosei K1’s soon.

To create over 1 g of cornering capabilities Scot utilizes an RRE coil-over suspension with custom-valved Bilstein front struts and GAB Adjustable rear shocks. RRE’s own “Anti-toe” rear lower control arm modification and front Adjustable Camber Plates were also added. A Suspension Techniques rear antisway bar and Racer Design front and Extreme Motorsports rear strut tower braces help reduce chassis flex. To help shave speed rapidly Powerslot rotors with Axxis Metal Master pads and Goodridge stainless steel lines are also used.

With the talented Road/Race team Scot has truly created one super car for much less than a supercar (with even more performance to boot). Beware exotic car owners, your large checkbooks can’t compensate for this little black beast and sooner or later its owner will have his sights set on you. For more info visit Scot’s site at www.dsmporn.com

| Car Specs | |

| 1994 Mitsubishi Eclipse GSX | |

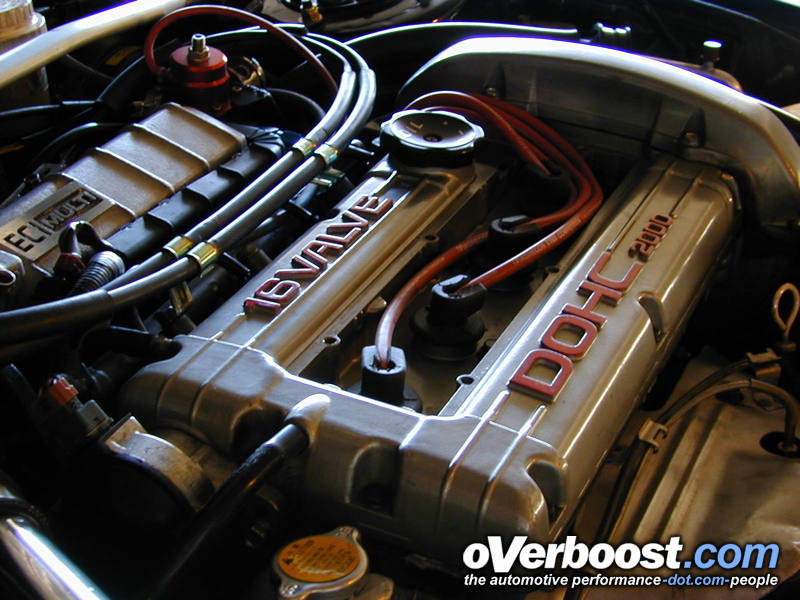

| Engine Type: | DOHC 16-valve four-cylinder |

| Engine Mods: | Ported and polished factory head; HKS Metal Head Gasket; ARP Head Studs; Ported ’95-Spec exhaust manifold; ported throttle body elbow and MAF Sensor; Web Cams 264 Intake, 272 Exhaust; S&B Air Filter; Texas Turbo Frankenstein Stage 2 Turbo, Ported, 10 Degree Clip; “crushed” stock Blow-off valve; TIAL External Wastegate; HKS front mount intercooler; Intercooler sprayer (Home Depot); RRE intercooler piping; Buschur Racing Polished upper intercooler piping; 3-inch RRE O2 Eliminator Downpipe; MSD DIS-2 Ignition Amplifier and 2 Stage Rev Limiter; Magnecore plug wires; NGK BP7E plugs; Ported O2 sensor housing; RRE “Racing” drop in radiator replacement; CarTech External Adjustable Fuel Pressure Regulator; Walbro 255Lph HP in-tank fuel pump (Hardwired); Blitz 660cc injectors; Random Technology 3-inch high-flow catalytic converter; 3-inch RRE exhaust with Dynomax SuperTurbo muffler. |

| Engine Management: | TechnoMotive Stage III ECU (No Fuel Cut) TechnoMotive Data Logger; A’PEXi AFC |

| Drivetrain: | Five-speed manual transmission with Redline MTL; Quaife Torsen-style center differential with Redline Shock-Proof; ACT 2600 Street Disc Clutch with lightened flywheel |

| Suspension: | RRE coil-over suspension (375 lbs front, 425 lbs rear) with custom-valved Bilstein front struts and GAB Adjustable rear shocks; RRE “Anti-toe” rear lower control arm modification to; RRE front Adjustable Camber Plates with upgraded Perches; Suspension Techniques 1.25-inch rear antisway bar with polyurethane bushings; Racer Design front and Extreme Motorsports rear strut tower braces |

| Brakes: | Powerslot rotors; Axxis Metal Master pads; Goodridge stainless steel lines |

| Wheels: | Street – SSR Integral 17×7; Circuit – Prime 5-Star 16×7; Drag – ’94-Spec Mitsubishi Eclipse GSX 16×6 |

| Tires: | Street – Bridgestone Potenza RE730 All-Season 225/45ZR17; Circuit – Kumho VictoRacer V700 R compound or Toyo Proxes RA1 tires 225/50R16; Drag – Dunlop SP8000 205/55R16 |

| Exterior Mods: | 1997 Montero Sport Mitsubishi logo; clear turn signal lenses |

| Interior Mods: | Corbeau Targa Racing Seats and Schroth AutoControl Harnesses; RAZO billet aluminum pedal set |

| Mobiletronics: | GReddy Turbo Timer and Digital EGT gauge; AutoMeter Boost gauge; Radio Shack intake temperature gauge; narrow range LED A/F Meter (.70-.95 Volt); A/F Ratio digital-volt meter; Pioneer DEN-245 head unit |

| Sources | |

| DSM Porn Road Race Engineering Technomotive ECUs |

Sport Compact Car Magazine – Project Mazda 323 GTX: Part 1

Here is Josh Jacquot’s Project 323GTX. We no longer sell parts for this car since they have to be custom made on the car in the shop. But since I got my start working on AWD rally cars on the 323 GTX working for Rod Millen back in1990 I always have aspecial sentiment for these fun little cars.

In this article we helped the SCC Mag guys with getting acquainted with the car and basic maintenance.

Sport Compact Car Magazine – August 2000

Writen By Josh Jacquot

Photography by Les Bidrawn, Josh Jacquot

Reprinted with permission

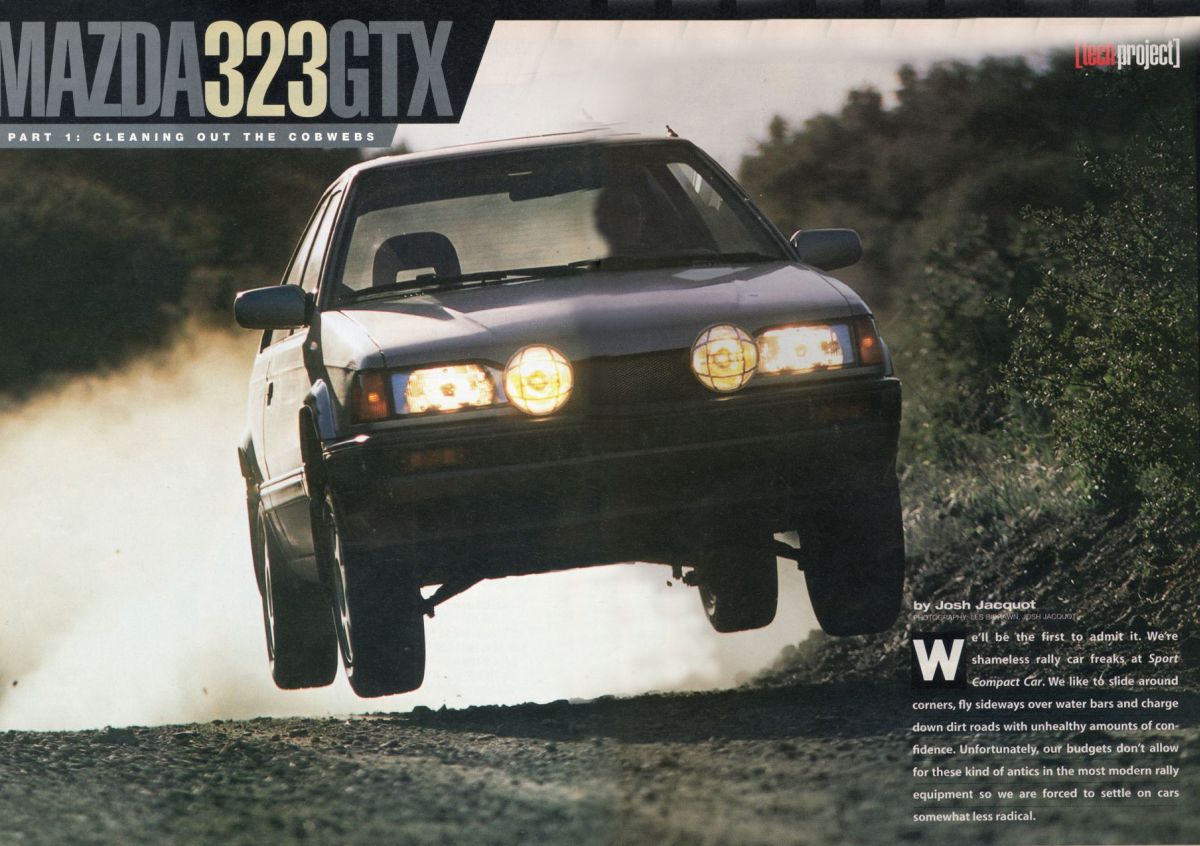

We’ll be the first to admit it. We’re shameless rally car freaks at Sport Compact Car. We like to slide around corners, fly sideways over water bars and charge down dirt roads with unlealthy amounts of confidence. Unfortunately, our budgets don’t allow for these kinds of antics in the most modern rally equipment, so we are forced to settle on cars somewhat less radical.

In this case, our choice for old-school rally equipment is a 1988 Mazda 323 GTX. With only about 1,200 of these cars sold in the United States in ’88 and ’89, they are a rare breed. We’d normally feel guilty about beating the life from a car this rare, but since ours was mostly dead when we bought it, we figure instilling a little rally car life back into its veins is the best thing we can do. Besides, its body is in fairly rough shape to begin with, so don’t plan on seeing pages of pretty pictures touting our GTX’s beauty. It’s not the best-looking SCC project car, but it may be the most functional.

Goals

Since we are appealing to an exceptionally small crowd with the GTX, we’re going to keep this buildup short. This installment we’ll explain a few of the rudimentary problems every GTX owner has faced or will face in the near future as their car shows the signs of age and high mileage. After dealing with the most nagging GTX problems, we’ll address the power issue over the course of a few more installments. When we’re finished, we should have turned a car with one wheel in the grave into a reliable, low buck hot rod.